Just before the elections, I had made an observation about the various failures of capitalism. Actually, it was an observation I had made before:

Think of this as an extension of D’JEver Notice? I, in which I made the point that each one of the industries that have “let us down,” if you take the time to inspect how that industry works and how it has morphed in recent history, you find it fails to stand as an example of the weaknesses of capitalism because it no longer adheres to any capitalist model. You have education, healthcare, the world oil market, and — since I wrote that above installment, which has turned out to be prescient — we’ve had this huge ol’ dealy-do with the subprime lending mess.

Capitalism didn’t create those problems. It didn’t leave us; we left it. We started messing around with some cross-breeding against the marxist way of life and that is when the real problems started.

Now there’s an election upon us in which we get to figure out an answer to the central question: Are we ready to give up on capitalism? Are we ready to put the socialists in charge of our government, unopposed, when they aren’t even ready to admit they’re socialists? And it occurs to me:

Capitalism is “failing” because we have seen it fall short of a standard that is so inherently silly, we cannot even say what it is, out loud, and still preserve a healthy, decent sense of shame. That standard is this:

To motivate all those involved in a financial transaction, to act in the interests of other parties similarly involved, to the detriment of their own.

Yesterday, Charles Krauthammer came up with some constructive criticism for the democrat party regarding what they should do with Obamacare: Junk it, and come up with an “Obamacare 2.0.” It’s not lost on me that as you read through Krauthammer’s piece, it almost comes through as an entirely unintended subtext — which it isn’t — that what’s good for the democrat party is bad for everyone else, and vice-versa. Krauthammer’s closing uppercut makes it clear that a “public option” to ensure that “everyone” receives the care they need, is a fool’s dream regardless of who wants who to win: “Look at Canada. Look at Britain. They got hooked; now they ration. So will we.”

Ezra Klein took exception to this:

So do we. This is not an arguable proposition. It is not a difference of opinion, or a conversation about semantics. We ration. We ration without discussion, remorse or concern. We ration health care the way we ration other goods: We make it too expensive for everyone to afford.

Klein then uses some statistics to create a beautifully symmetrical Rorschach pattern: “38 percent of Britons and 27 percent of Canadians reported waiting four months or more for elective surgery. Among Americans, that number was only 5 percent…24 percent of Americans reported that they did not get medical care because of cost…In Britain and Canada, only about 6 percent of respondents reported that costs had limited their access to care.”

It reminds me of what President Obama said about public sector vs. private sector competition, comparing it to the postal service co-existing with private carriers with his crack about the “Post Office always having problems.” The point is supposed to be universal coverage; uni-coverage that won’t make us sorry we asked for it. Klein, like Obama, seems to have lost track of what he’s trying to argue here. Obama was trying to sell us a public option as the answer to our problems, and to buttress his point, look at the Post Office that’s always having problems! Klein, on the other hand, if I’m reading him right — his message is one of “Sure there are long waits when everybody is covered, but that’s okay because everybody will be covered…okay, they won’t be…but things are just as bad now, so let’s just change the badness without expecting anything to get better, and you see, we’ve just gotta do this.”

Or…something like that.

The commonality between the two, is this dogged determination to defeat each argument from the opposition by any means, usually with some technicality that might look good on paper but logically ends up being entirely meaningless.

The trouble they’re having, is that with a radical change to America’s health care system, there is a REAL possibility that REAL people might get REALLY hurt — and everybody understands this. That motivates people to think differently. You tell people “The reason the economy sucks is that we aren’t taxing the rich enough, what we need to do is tax them completely into oblivion so we don’t have any rich people anymore”…and people buy into that. Why shouldn’t they? You’re admitting you’re hurting someone, but that’s okay because it’s someone they’ll never, ever meet…

So they buy into your fairy tale: We must destroy the economy in order to save it.

When this obvious fissure between your fairy tale, and truth itself, threatens to hurt them, though — this all changes. This is a situation somewhat like trying to figure out if there’s a scorpion’s nest under the backyard structure on which their kids play. It makes people think differently. Better. It renews their bond with the plane of reality, and responsible planning. The cold hard fact of the matter is this: People are much more interested in reality when it directly benefits them. Not the other guy. Them.

And so this dog won’t hunt. Let’s turn everything around, because too many people are denied care. But after we turn everything around, an equal number of people will still be denied care…but that will be much better because…uh…where was I going with this?

As for the substance of Klein’s international comparison, Ronald Bailey takes him to task in Reason:

Like most left-leaning folks, Klein clearly doesn’t know the definition of rationing. Take this one from Britannica:

Government allocation of scarce resources and consumer goods, usually adopted during wars, famines, or other national emergencies.

Klein evidently thinks that market outcomes that he dislikes mean that government should step in and impose outcomes that he does like. All right, let’s admit it; the health insurance market and the rest of health care are royally screwed up as a result of decades of government interventions and mandates. Consequently we don’t actually find the usual benefits of falling prices and improving products and services that we experience in normally operating markets where robust competition and choice reign.

As I explained in an earlier column where I tried to clear up New York Times economic columnist David Leonhardt’s similar confusion over rationing:

…what is rationing? Leonhardt is correct when he writes, “In truth, rationing is an inescapable part of economic life. It is the process of allocating scarce resources.” The crucial question that Leonhardt misses is that “rationing” depends on who is allocating the scarce resources. It’s not rationing if an individual decides to spend his money on a 16-ounce steak—but it is rationing if he can only purchase a USDA prime rib eye when he has a coupon issued from a government agency. In other words, true rationing occurs when individuals are forbidden from spending their money on products or services they want to buy.

Imperfect as private health insurance markets are, if a customer [or his employer] doesn’t like the decisions made by Blue Cross Blue Shield, Kaiser Permanente, or Golden Rule insurance bureaucrats, he can look elsewhere for his health insurance coverage. But if the government health care scheme becomes a monopoly, when the bureaucrats at the new Health Benefits Advisory Committee decide that a treatment should be withheld, that treatment will be withheld. That’s rationing.

I concluded:

“Americans should get the first chance to limit their own health spending,” Rep. Jim Cooper (D-Tenn.) observed recently. “Once they learn the true cost of what they are buying, share a larger portion of the cost, and can judge the benefits—if any—of treatment options, then they will choose more wisely than the government.” He’s right. Congress should think about “rationing” health insurance and health care the old-fashioned way—through the market.

But through the usual lack leftwing lack of imagination and a truly touching and naive faith in the efficacy of top/down government “solutions,” Klein ends up advocating for government rationing and for imposing a government monopoly on health care, instead of for more competition and choice.

This all goes back full-circle, to the original point I made about these industries that demonstrate the failures of capitalism by letting us down so badly — but do not really stand, any longer, as models of what we have in mind when we talk about “capitalism.” Health care, like home-equity lending, has been stuck in that whirlpool for a very long time now. In my own way, I know this first-hand from my twelve years plus-something in the health care industry. Even Information Technology geeks, at some point, have to be concerned with the health of the industry that provides the wealth in their paychecks…and from the inside, I could see that industry was not terribly impacted, like a true capitalist mechanism, with the “real” costs of providing quality care.

It was the “general” expense that represented the big headaches, the sorry-no-raises-this-year, the apprehension about the next round of layoffs. The layers of “oversight” and “regulation,” the tort system, the latest political hiccup that got Congress suddenly interested in our industry as a whole. That is what increased the difficulty of operating, and it wasn’t terribly hard to see after awhile.

With that experience behind me, I’m still waiting for someone to coherently explain how a public option would streamline this. So far, all I’m hearing is the Klein argument, that equal numbers of people would be left uncovered, but somehow more artfully. And the Obama argument, that I should look to the Post Office as my harbinger of what’s to come, with all the problems they keep having.

I’m not finding these arguments terribly convincing, I must say. And I don’t think I’m alone.

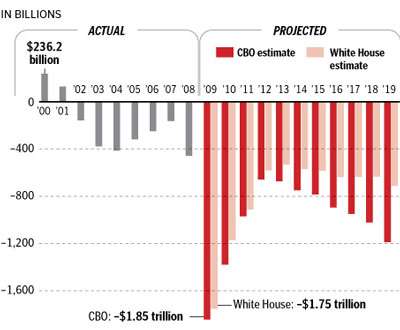

Or, we can rely on simple mathematical concepts. The feds did pump a lot of money into our banks…but what the feds pumped into our banks…came from us in the first place. That, or it was borrowed. Our simple mathematical concept therefore is —

Or, we can rely on simple mathematical concepts. The feds did pump a lot of money into our banks…but what the feds pumped into our banks…came from us in the first place. That, or it was borrowed. Our simple mathematical concept therefore is —

…and the “

…and the “

Think of, think of, think of. Think of everything except whether the idea is a good ‘un or not. As I

Think of, think of, think of. Think of everything except whether the idea is a good ‘un or not. As I  It’s a

It’s a