This blog, which nobody actually reads anyway, is named after a mathemetician, library administrator and brainy-guy who lived around two hundred years before Christ and figured out the size of the earth without the benefit of telescopes, spaceships or any other such gadgetry. This was not a disciple of Aristotle or Plato or Socrates; he was the head honcho of the Library of Alexandria, and had just about as much business measuring the planet’s size as…well, as a software engineer has figuring out that liberalism is bad for you. He figured out the size of the planet on which we live, and he did it by peeking into water wells. He made do with what he had, and used careful, responsible thinking to figure out and validate a fact about something much bigger than he was.

As such, this blog’s primary obsession is with a point-of-view about life itself: Information is to be taken in, worked over, and harvested into yet more information, by whoever among us possesses the mental skills do it. It is not to be cloistered behind ivy-covered walls, for the consumption of elites who periodically emerge from behind the walls to tell the rest of us what to think. We all have the responsibility of maintaining an inventory of what we know, versus what we do not know, and from that inventory figuring out what’s really going on. And, from that, figuring out what to do about it.

As such, this blog’s primary obsession is with a point-of-view about life itself: Information is to be taken in, worked over, and harvested into yet more information, by whoever among us possesses the mental skills do it. It is not to be cloistered behind ivy-covered walls, for the consumption of elites who periodically emerge from behind the walls to tell the rest of us what to think. We all have the responsibility of maintaining an inventory of what we know, versus what we do not know, and from that inventory figuring out what’s really going on. And, from that, figuring out what to do about it.

And so the time has come to opine on the Gates affair. You have already heard the background. Professor Henry Gates, a professor of Ethnic Studies at Harvard and a personal friend of our President, was questioned by a policeman inside his own home after breaking into it. The policeman was called by a well-intentioned neighbor who observed Gates and his driver forcing a door that had jammed shut.

I’ll leave the rest of the background to Leonard Pitts, who in my opinion has done a wonderful job of accurately recording all the facts, those which are in dispute as well as those which are not, and drawing all of the wrong conclusions from them.

The incident began when Gates, returning from a trip to China, found his front door jammed. When he and his driver tried to force it, a neighbor, thinking it a burglary, did the right thing and called police. [Sergeant James] Crowley responded, finding the driver gone and Gates inside. There are two versions of what happened next.

Police say Gates refused to comply with Crowley’s order to step outside, initially would not identify himself and became belligerent, yelling that Crowley, who is white, is a racist, that he didn’t know who he was messing with and that this was only happening because Gates is black.

Gates says he promptly produced his driver’s license and Harvard ID, that the officer refused to provide his name and badge number, and that he could not have yelled anything because he has a severe bronchial infection.

This much is not in dispute: Gates was arrested after providing proof he was lawfully occupying his own home. The police report says he was “exhibiting loud and tumultuous behavior in a public place.” That being his own front porch. Small wonder the charge has been dropped.

And here, Sgt. Crowley’s defenders would want you to know he is not some central casting redneck, but an experienced officer who has led diversity workshops.

On the other hand, Gates is hardly Sister Souljah himself. Rather, he is a man who did the things African Americans are always advised to do: work hard, get a good education, better yourself, only to discover that in the end, none of it saved him. In the end, he still winds up standing on his front porch with his wrists shackled.

Pitts, here, is guilty of peeking into one water well but not the other; he reaches whatever conclusion he wants to reach, relying on his personal sentiments rather than reason and logic. He fails to realize — there is a reason people are pointing out Sergeant Crowley works his diversity training workshops, and that reason is because Professor Gates was railing away about the Sergeant’s passionate racism. Crowley’s resume does not resoundingly falsify this; but it certainly deals the theory a blow, from which it never actually recovers. As such, it is revealed to anyone paying attention for what it is. The product of the overactive imagination of an Ethnic Studies professor with a giant chip on his shoulder. None of this matters to Pitts, who is arguing — essentially — that because Gates works in a prestigious university and relies on a cane to walk, dang it, he must be in the right here.

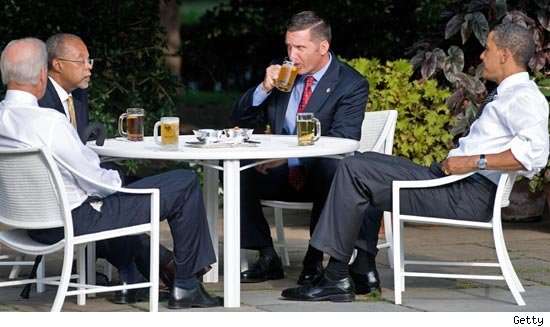

Not that too many other folks are doing a better job thinking this thing out. Last week, President Obama made sure we’d be talking about this for awhile, when he responded at length, Leonard-Pitts-style, to a question about it. During a press conference about health care.

I said Leonard-Pitts-style, and perhaps that is unfair to Mr. Pitts. Pitts had access to all the information, or at least, honestly thought that he did; President Obama, on the other hand, conceded that He didn’t have all the facts, but made up His mind anyway:

The final moments of President Obama’s press conference last week have gotten the most attention, and some of the president’s supporters have wondered whether his big-footed interference in the Harvard professor’s melodrama has overshadowed his push for health-care reform.

But the president’s response to Gatesgate actually sheds a lot of light on his approach to health care and other issues, for this reason: Obama adopts his positions before knowing what he is talking about. To be fair, Obama admitted as much, at least as far as Gates was concerned. “I don’t know all the facts,” he acknowledged, before launching into a lecture (later retracted) about the “stupidity” of the Cambridge police (while misrepresenting what had happened).

How could he not have known all the facts? Press secretary Robert Gibbs mentioned on Fox News Sunday that the Gates matter was one of the issues the White House press operation had briefed the president on before the press conference. Numerous accounts of the imbroglio were available online — though the president need only pick up the phone to get all the information he wants.

He didn’t want information. He preferred his comfortable, prejudiced view.

This is worth bearing in mind as the country takes a good, hard look at the president’s plans for health-care reform. On the day he announced support for embryonic-stem-cell research, Mr. Obama also signed an executive memorandum declaring that in the Obama administration, “We [will] make scientific decisions based on facts, not ideology.” And yet, his health-care proposals — or rather the congressional ideas he has endorsed — seem to skirt facts and evidence at every turn.

A leader for our times?

Well, perhaps so. We all have this tendency to make up our minds that the earth is as flat as a pancake, before we’ve peeked into our first water well. From then on, as the evidence rolls in the most common error is to select said evidence. Cherish whatever substantiates this pre-selected conclusion of ours, and discard whatever may contradict it outright, or pose a simple challenge to it. This is the First Instinct fallacy, and it holds an appeal to us because it makes it easy to think we can sort of bumble into the right answer to something, and formulate a plan just as beneficial to our interests as something else constructed only with a lot of stewing and mental effort. It makes all this hard work seem unnecessary. Just go with your gut, and that’s probably right.

Well there’s a price to be paid for that: You have to wait around for someone to travel around the world in order to know how big it is. Of course, you can speculate uselessly on that to your heart’s content. Up with your side, down with the other guy’s side…you can think what you want. But you might have to backpedal. You might have to go the Obama route. You might have to resort to silly platitudes to get the shining spotlight off you, and issue your calls for a national dialogue. The disadvantage there, of course, is that platitudes eventually wear out…or at least, they might. Weren’t we all calling for a national dialogue on race right after Obama’s pastor was revealed to be a racist asshole? Yes, it seems like just yesterday. We were congratulating The Holy One for another fine speech, and suddenly everyone stopped talking about Jeremiah Wright and “God Damn America.” We stopped talking about race, too, at least in ways that might have any effect on the Obama campaign other than to help it along. National dialogue my left nut. That’s just a mantra, nothing more.

Here’s the trouble with the way we’re processing this.

Here’s the trouble with the way we’re processing this.

First of all, the one thing you can do before any of the information rolls in, is to make a list of the possible conclusions. That’s quite justifiable, and even preferred. There aren’t too many: Professor Gates is in the right, or Sergeant Crowley is in the right. Add to that this popular “mixed bag” thing a lot of people are conjuring. It’s brain-dead, but there’s legitimacy to it as a possibility. They’re both equally wrong; they’re both wrong, but Gates is more wrong than Crowley; they’re both wrong, but Crowley is more in the wrong than Gates. That’s three, in addition to the two obvious extremes. Five total. Strong verdict for Gates because Crowley is a racist dickhead, milder verdict for Gates, toss-up, milder verdict for Crowley, strong verdict for Crowley because Gates is a troublemaker.

Well here’s the trouble. And this is what our “national dialogue” really has to address, in my view. I haven’t refined these possibilities overly much, opting instead for a big-pixel, thirty-thousand-foot view. But look what we have happening here: Our nation, and therefore our modern society that is a part of it, is burdened with this history of oppressing persons of color. Enslaving them, segregating them, discriminating against them, engaging in nasty shenanigans to keep them from voting when they should’ve been able to, and arresting them for nothing. And because of that, we sometimes act in haste to try to abjure any notions that any individuals among us might be racists…save for those who are advancing something we’re trying to stop. It’s the thirty-thousand-pound napalm MOAB of our modern times. Get this ordinance dropped, and your enemy disintigrates. Love the smell of napalm in the morning.

And so the Gates affair is a rather handy lesson for us. It puts the big reveal on what a wonderful job we’ve done, closing our eyes to the truth.

It’s the last of those categories, you see. The idea that the cop can be completely in the right, and the professor could have been completely in the wrong. Most of the folks who’ve already commented, have been caught off guard. In their haste to be exonerated from this lingering suspicion of racism, it has become popular to lop off that wholly legitimate conclusion even from the list of trivial possibilities. Something must have been wrong with what the cop did. There must have been an error made somewhere!

Trouble is, all of the evidence that has been wandering on in to view, be it at a quick trot or at a slow plodding, once it’s verified the bulk of it seems to support that final conclusion, that Professor Gates is as racially prejudiced as any American has been in modern times. Most problematic in this evidence is the report that Gates, once drawing his own conclusion that he was being unfairly hassled because of the color of his skin, nevermind whether that was with justification or not — started mouthing off at a cop. This is where my sympathy falls away. You don’t do that, regardless of the color of your skin. You just don’t get to walk away from that. And how did Gates draw these conclusions, anyway? It seems to say a lot more about Gates himself than about any situation in which he found himself. He has a personal complex about this stuff, and once finding himself being questioned by a policeman, injected race into the situation when nobody else had.

So at this point, the logically strongest conclusion is this: that Professor Gates created this incident.

It has become an unfortunately widespread weakness to close one’s eyes to this as a possibility, though, and therefore to any evidence that might lead to it. All too often, that has been eliminated, then First Instinct takes over. This is a disservice to Sergeant Crowley and to police everywhere, especially police who serve in urban areas periodically unsettled with racial tension. Too many among us fail to see that on an incident-to-incident basis, the officer on the scene just might have handled things properly. It’s possible. It is a possibility. We just can’t see it, because we’re too busy being sensitive. The cop must be wrong, somehow; a little, or a lot, but he must have done the wrong thing. Now let’s round up some facts to back that up.

We all know that’s not the way to go about this. But many are going to be preoccupied by pointing out it isn’t my place to be bringing any of this up. I’m a six-foot protestant white guy with all his limbs and twenty-one digits. This is none of my business.

Just like it’s none of a library administrator’s business to figure out the world is 40 thousand kilometers in circumference.

I can see how, in the minds of some, that might appear to be a legitimate thing to point out. But…it doesn’t make the world flat, now does it?

If you were to have jotted these events down in manuscript form before they actually occurred, no publisher of fiction would accept it. It’s all too surreal, too absurd, too astonishing, too preposterous. It would never happen in real life. This is a new low nadir. This takes the cake. It descends beneath “[illegal aliens] are doing the work Americans won’t do.” It descends beneath Howard Dean yelling “YEEEEAAAARRRGGGHHHH!!!!” It descends beneath John McCain suspending his campaign to fix the mortgage crisis. It descends beneath John Edwards screwing around on his cancer-stricken wife, and Gov. Sanford hiking in the Appalachians.

If you were to have jotted these events down in manuscript form before they actually occurred, no publisher of fiction would accept it. It’s all too surreal, too absurd, too astonishing, too preposterous. It would never happen in real life. This is a new low nadir. This takes the cake. It descends beneath “[illegal aliens] are doing the work Americans won’t do.” It descends beneath Howard Dean yelling “YEEEEAAAARRRGGGHHHH!!!!” It descends beneath John McCain suspending his campaign to fix the mortgage crisis. It descends beneath John Edwards screwing around on his cancer-stricken wife, and Gov. Sanford hiking in the Appalachians. If, when we as individuals make dumbass decisions, we can expect to deal a severe injury to ourselves but to none of our neighbors — then we have the makings of a free society. If, on the other hand, our reprehensibly bad judgment poses a danger to others whenever it poses a danger to us, then our freedom is already gone. All the intermediate steps that ensue…the statist politician or advocate making his way to the microphone, imploring us to accept the next nanny-state law, the strategically-worded polls that draw pre-calculated answers saying people are oh so worried, all the canned speeches about the status quo being unacceptable, the committee votes, the floor votes, et cetera…these are nothing but inevitable and meaningless milestones, hash marks along the swing path of the wrecking ball. Once the foolishness of one can be expected to impact the welfare of the many, we aren’t free anymore, it’s all over but the shouting and the weeping.

If, when we as individuals make dumbass decisions, we can expect to deal a severe injury to ourselves but to none of our neighbors — then we have the makings of a free society. If, on the other hand, our reprehensibly bad judgment poses a danger to others whenever it poses a danger to us, then our freedom is already gone. All the intermediate steps that ensue…the statist politician or advocate making his way to the microphone, imploring us to accept the next nanny-state law, the strategically-worded polls that draw pre-calculated answers saying people are oh so worried, all the canned speeches about the status quo being unacceptable, the committee votes, the floor votes, et cetera…these are nothing but inevitable and meaningless milestones, hash marks along the swing path of the wrecking ball. Once the foolishness of one can be expected to impact the welfare of the many, we aren’t free anymore, it’s all over but the shouting and the weeping. Well, I’m of two minds about it. The girl is horribly miscast, but at least she does know how to act, kinda. Did I say horribly miscast? I meant awfully, terribly, reprehensibly, stink-on-wheels miscast. I think they broke the mold before they made Michael Bay. The man knows how to blow things up, and he knows how to have lots of guys walk in slow motion toward the camera in a classic “power walk” just before they face certain doom. But he couldn’t assemble a female character to save his life. He doesn’t seem to keep in mind if he’s developing a nice-girl, a bored-housewife, a bitch, a vamp, a hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold, an evil-stepmother, a dowager, a princess, a lady-of-the-lake, Juliet, Marion Ravenwood, Lieutenant Uhura, Scheherazade, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. It’s like, to him, they’re all just one male stock character with a few different body parts.

Well, I’m of two minds about it. The girl is horribly miscast, but at least she does know how to act, kinda. Did I say horribly miscast? I meant awfully, terribly, reprehensibly, stink-on-wheels miscast. I think they broke the mold before they made Michael Bay. The man knows how to blow things up, and he knows how to have lots of guys walk in slow motion toward the camera in a classic “power walk” just before they face certain doom. But he couldn’t assemble a female character to save his life. He doesn’t seem to keep in mind if he’s developing a nice-girl, a bored-housewife, a bitch, a vamp, a hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold, an evil-stepmother, a dowager, a princess, a lady-of-the-lake, Juliet, Marion Ravenwood, Lieutenant Uhura, Scheherazade, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. It’s like, to him, they’re all just one male stock character with a few different body parts. It would also empower regulators to ban pay structures that encourage “inappropriate risks by financial institutions … that could threaten the safety and soundness of covered financial institutions, or could have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability.”

It would also empower regulators to ban pay structures that encourage “inappropriate risks by financial institutions … that could threaten the safety and soundness of covered financial institutions, or could have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability.”

As such, this blog’s primary obsession is with a point-of-view about life itself: Information is to be taken in, worked over, and harvested into yet more information, by whoever among us possesses the mental skills do it. It is not to be cloistered behind ivy-covered walls, for the consumption of elites who periodically emerge from behind the walls to tell the rest of us what to think. We all have the responsibility of maintaining an inventory of what we know, versus what we do not know, and from that inventory figuring out what’s really going on. And, from that, figuring out what to do about it.

As such, this blog’s primary obsession is with a point-of-view about life itself: Information is to be taken in, worked over, and harvested into yet more information, by whoever among us possesses the mental skills do it. It is not to be cloistered behind ivy-covered walls, for the consumption of elites who periodically emerge from behind the walls to tell the rest of us what to think. We all have the responsibility of maintaining an inventory of what we know, versus what we do not know, and from that inventory figuring out what’s really going on. And, from that, figuring out what to do about it. Here’s the trouble with the way we’re processing this.

Here’s the trouble with the way we’re processing this. Concerns like

Concerns like

So

So  7. Choose your motor oil wisely.

7. Choose your motor oil wisely.

And the GOP wants to know how to rebound. Hey guys. Here’s a wild, crazy idea: How about becoming the party of evidence? We saw last November how the other folks do it…Obama gives some speeches without saying anything — some fainting, “There’s Just Something About Him!!” and some pants-wetting — done deal. How about distinguishing yourselves from the competition by showing us how grown-ups think?

And the GOP wants to know how to rebound. Hey guys. Here’s a wild, crazy idea: How about becoming the party of evidence? We saw last November how the other folks do it…Obama gives some speeches without saying anything — some fainting, “There’s Just Something About Him!!” and some pants-wetting — done deal. How about distinguishing yourselves from the competition by showing us how grown-ups think?