Tough to come up with a headline/post for this one…not so tough to excerpt. P. J. O’ Rourke, at his finest (hat tip to Maggie’s Farm):

When did America quit bragging? When did we stop punching hardest, kicking highest, roaring loudest, beating the devil, and leaving everybody else in the dust?

We’re the richest country on earth—four and a half percent of the world’s people producing more than twenty percent of the world’s wealth. But you wouldn’t know from the cheapjack spending squabbles in Congress. We possess more military power than the rest of the planet combined. Though you couldn’t tell by the way we’re treated by everyone from the impotent Kremlin to the raggedy councils of the Taliban. The earth is ours. We have the might and means to achieve the spectacular—and no intention of doing so.

:

For fifty years, from 1931 to 1981, the US had the longest suspension bridge spans, first with the George Washington Bridge, then the Golden Gate, then the Verrazano-Narrows. Now even Hull, England, has a more spectacular place to make a bungee jump. Although we are in the lead with that. The elasticized drop from Colorado’s Royal Gorge Bridge is 1,053 feet long, showing that whatever America has lost in technological superiority we’ve made up for in sheer idiotic behavior.

Speaking of which, there’s our space program, which has basically ceased to exist. We have a NASA that might as well have been dreamed up by Alger Hiss. In order for Americans to get to the International Space Station, they have to go to Russia.

And in order for Americans to get to the bottom of how the universe works, they have to go to Switzerland. We were planning to build a high-energy particle collider in Texas that would have had a circumference of fifty-four miles—three times the size and power of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva. But Congress canceled the project in 1993.

America has had plenty of reasons to abdicate the crown of accomplishment and marry the Wallis Simpson of homely domestic concerns. Received wisdom tells us that, in the matter of great works and vast mechanisms, all is vanity. The Nurek Dam probably endangers some species of Nurek newt and will one day come crashing down in a manner that will make the aftermath of Japan’s Fukushima tsunami look like an overwatered lawn. And we have better things to spend our country’s money on, like putting a Starbucks on every city block. But I suspect there’s a sadder reason for America’s post-eminence in things tremendous, overwhelming, and awesome.

My sad generation of baby boomers can be blamed. We were born into an America where material needs were fulfilled to a degree unprecedented in history. We were a demographic benison, cherished and taught to be self-cherishing. We were cosseted by a lush economy and spoiled by a society grown permissive in its fatigue with the strictures of depression and war. The child being father to the man, and necessity being the mother of invention, we wound up as the orphans of effort and ingenuity. And pleased to be so. Sixty-six years of us would be enough to take the starch out of any nation.

Smackdown…

America once valued the high-skilled. Now we value the high-minded. We used to admire bold ideas. Now we admire benign idealism. This doesn’t make us good, it makes us wrong. The bold can be achieved. Of the ideal, there is none in this life.

Trudging toward infinity versus trudging toward zero. The zero always seems easier because it’s closer, but the irony is that we destroy ourselves getting there because we have to abandon our creative energies. What do you do, the day after you’ve succeeded in approaching the zero? You become an embodiment of silliness, much like the dog that can catch the car. Seriously, what do you do? Nail it again?

So I would not put all the blame on the baby-boomers. How many Gen-X slackers do we have who want to fly to Mars? How many Millennials? This isn’t a problem with a generation, it’s a problem with an event.

Blogger friend Gerard linked earlier this month to some other, topical commentary:

Human capability peaked before 1975 and has since declined

I suspect that human capability reached its peak or plateau around 1965-75 – at the time of the Apollo moon landings – and has been declining ever since.

This may sound bizarre or just plain false, but the argument is simple. That landing of men on the moon and bringing them back alive was the supreme achievement of human capability, the most difficult problem ever solved by humans. 40 years ago we could do it – repeatedly – but since then we have *not* been to the moon, and I suggest the real reason we have not been to the moon since 1972 is that we cannot any longer do it. Humans have lost the capability.

Now, how did we get here exactly? Travel back to the early seventies by whatever time-travel vehicle is at your disposal: Books, retro DVDs ordered over the Internet, Netflix Instant. You have to wonder how we made it through the decade. It certainly doesn’t look like the apex of hundreds of thousands of years of human achievement, by any stretch.

Think about a baseball reaching its very peak in the trajectory after it has been thrown. Once it reaches that point, it plunges to Earth again — but not because it hit something, right? No, it runs out of kinetic energy after a cumulative depreciation. The net effect has been applied since it left your fingertips, about a second or two previous, and it is achieving relevance at the peak now that it has succeeded in changing the vertical direction from an up to a down. In fact, at the apex there is no meaningful event taking place at all, other than that change from an up to a down, and that change is merely a manifestation.

Point being: As we look for an event, even accepting the idea that the zenith was around the time of the moon landings, we need to look for something prior to that. Possibly preceding it by several years. We landed on the moon in spite of something that already had a good head start gnawing away at us. Since then, all this destructive force has done, is grow some more.

This doesn’t take too much careful thought. But it does take some.

I see lately we are very interested in changing paradigms. Coming up with a new transistor that is half as big as the one that came before; that is not a realistic vision for the pie-eyed dreamy kid building things in his garage. Such an achievement would be measured on the scale of nanometers now, manufactured in a million-dollar clean room owned and maintained by a giant public or private organization. Creating a whole new way of doing the switching, that might capture some imagination but not enough for actual implementation because, again, resources. Part of what has left us, seems to be the standing-on-shoulders-of-giants thing: I’m going to take what this other guy did, and make it look like nothin’. But when I accept my award I’ll be sure to call him out. That’s gone. Nobody wants to head down the same direction a further distance, they just want to head down a whole new direction.

By itself, that is harmless. In fact, by itself, that is the stuff from which big, bold dreams are made: Why fly over the Atlantic? Why not build a tunnel under the whole damn ocean? But there’s another problem. Heading off in a whole new direction is a productive exercise only when there’s a sense of purpose to it. A constructive sense of purpose.

Look at all the superheroes in comic books being rebooted right now. We could do another rant about Wonder Woman being put in long pants again, but now it’s a lot more characters than just her (although, since she’s always been lacking in definition vis a vis super-powers, secret identity, is she bullet proof, et al, she’s by far the best example of the problem). Superman is being rebooted in both the comic books and in the movie. To what end? He was rebooted just a few years ago. Ditto for Batman. Ditto for The Avengers over in the Marvel universe. And Star Trek. Reboot, reboot, reboot, reboot. Everybody wants to be bold. Well, boldness is good. But when you’re working from a blank slate just to avoid the research that would become obligatory if you were to build on top of what was there before, it isn’t bold anymore. It’s just lazy.

The litmus test is: Was the boldness built on top of a definable purpose. Of course, every artist and every one of their sympathizers is going to answer in the affirmative. No exceptions. But what is the purpose? Does it have any real passion behind it? “To create a Green Lantern that is in harmony with the values and concerns of the new generation”…that’s a cop-out. Fiction, by its very definition, is an inconsequential quibble of course. But it does carry the potential to say something about us, as it morphs to suit our evolving tastes. And what this says, here, is: We don’t want our parents’ superheroes. We’ll accept their names and their logos and their rough, general appearances, but we want new substance. We demand an imprinting of modern times. Aquaman using a cell phone, Invisible Girl using an iPad, not a soul on the bridge of the Enterprise over twenty-eight.

In a nutshell: Our culture borrows from what came before, only when it spares us work. Not when it challenges us.

We are still excited about building new things, but the new things we build are emblematic. They are signatures. They exist to say, primarily, “so-and-so was here.” They do not exist to make new things possible for others who will come along later. Quite to the contrary, being signatures, there will necessarily be some resistance to a wave of successors building on top of them. So look for more superhero-rebooting in the generations ahead. Our creativity is being channeled into distinguishing ourselves, from others, and not to expand the capacity of the human potential.

And here we come to the crux of the matter: The desire to distinguish ourselves from others necessarily must carry a hostility toward those others. Any remnants left in your project that are identifiable with what someone else has done, or is doing, become undesirable. So you need to purge it of the residue of not only your predecessors, but also of your rivals.

Besides of which, it’s lazy. The two toughest parts of building something that actually works, like a good economy, or computer hardware or software component, are: Recognizing that similar things are similar, and recognizing that different things are different. That takes some careful mental discipline when you work way down in the details. With this business of building uniquely identifying insignias, in which we all become Ozymandias, the job distills down into one step: Make your thing different. Job done. Who cares if it works or not. In the case of movies, there’s supposed to be some pressure on that the producer should make a profit; I’m sure that pressure is present in some sense, but it doesn’t have much of an instantly devastating effect when this bar isn’t reached.

We have this urban legend kicking around about the head of the Patent Office writing a letter to President McKinley, or Roosevelt, that this office should be closed down because “everything that could be invented, has been.” Perhaps, if it were true, the mistake would have been limited to merely writing prematurely. A century and some change onward, the electronic circuits are evolving still but much of this evolution has to do with integration, shrinkage, and some tricky particulars involved in 3D rendering; as far as the basic building-block science is concerned, people are more-or-less satisfied with it. The databases have been built, and indexed, and now they’re used to service these boiler room operators who so regularly violate the spirit, if not the letter, of the Do Not Call registry. The flat screen teevees, whether they are LCD or LED or plasma, work great. We use them to watch commercials that let us know how easy it is to sue somebody. Of course, we can skip past these with the DVR, but it takes some doing because this part is essentially an “arms race” between two technology consumers that are motivated by competing interests. You don’t want to watch the commercial even if the advertiser wants you to, and the advertiser wants you to be forced to watch the commercial even though you’d rather not. So there’s a lot of inventiveness going on there, but it’s essentially going in a circle.

Oh, and we don’t want to pay for anything — whether you have the ability to skip past these commercials or not, it’s pretty hard to spend any block of time absorbing electronic media information, without hearing the phrase “find out if you qualify.”

We still like to build things. But we like to build things that say something about us, we’re not interested in building things so the other guy can build something. That makes us destroyers. Lazy destroyers.

And it is the laziest and most destructive among the lazy destroyers, who pack the biggest wallop of influence. This means that the greatest abundance of “creative” energy, is spent passing judgment on each other. This is supposed to be God’s job, and we see what a mess is made when man passes judgment on man. Four years ago, how often did we hear the upcoming Obama vote justified with the phrase, “there still is some racism out there.” Yeah…and? So? Four years later, the President is black, has racism ended? Anybody think so? Where are our bragging rights? Who likes us better? There’s a lesson there.

If we want to know where the racism is, we only need to ask Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton; they’ve made lifelong livelihoods out of pointing it out. Do you want your sons to turn out like them?

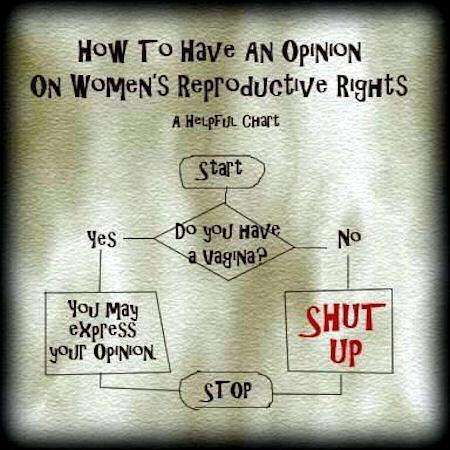

If we want to know where the sexism is, I guess we ask Sandra Fluke, or Hillary Clinton. You want your daughters to turn out like them?

We aren’t changing for the better, because too much of our effort toward this “change” involves placing authority in people we do not see as role models, people we do not want to become. See, there’s the big problem. When Bruce Charlton says:

50 years ago we would have the smartest, best trained, most experienced and most creative people we could find (given human imperfections) in position to take responsibility, make decisions and act upon them in pursuit of a positive goal.

Now we have dull and docile committee members chosen partly with an eye to affirmative action and to generate positive media coverage, whose major priority is not to do the job but to avoid personal responsibility and prevent side-effects; pestered at every turn by an irresponsible and aggressive media and grandstanding politicians out to score popularity points; all of whom are hemmed-about by regulations such that – whatever they do do, or do not do – they will be in breach of some rule or another.

…what he is talking about is a delicate formula involving man, name, hat, move. The man would become elected, or appointed, or perhaps move himself into, the position. The man would wear the hat. He already would’ve had the name, and he would have worked his whole life, before that time, to keep his name good. But he couldn’t make the move until he wore the hat, because the authority for such a decision belonged to the hat, not to him. So, the man with the name would put on the hat, and make the move. Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower launched Operation Overlord. Henry Ford started Ford Motor Company. Person did thing. Subject-verb-object.

These “dull and docile committee members” of whom the essayist writes, avoid doing things. They make their decisions with an eye toward, if someone in a greater position of authority asks which ass to kick, it won’t be theirs.

They are motivated by the destructive force which is currently acting as a cement to our building-block society. We’re looking for ways to distinguish ourselves without building anything. Got our eyes and ears out, keeping each other in line. Looking for a botched decision somewhere, some rule that wasn’t followed or interpreted correctly, or some “ism.”

That is how today’s man makes his name. That is the hat he wears, and he wears it from birth. Not “guy in charge of…” but, instead, passive tattle-tale. Use the hat to make the name, by tattling the right tale at the right time, as opposed to using the good name to earn the hat. And don’t make a move, whatever you do.

Which translates to: Build nothing. At least, build nothing but fashion. And don’t go destroying all the time, necessarily…but, by all means, keep your eye open for the opportunity.

“As a matter of cosmic history, it has always been easier to destroy than to create.”

— Leonard Nimoy as Spock in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

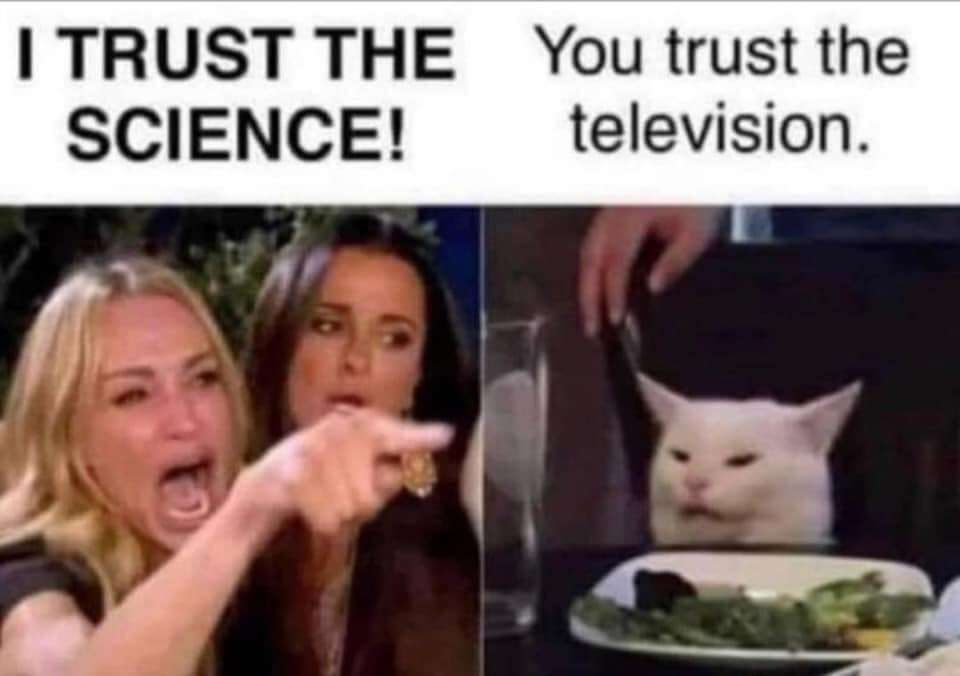

It is that last, paraphrased, comment that piques my interest here, specifically the very last raspy inquiry that I placed in the italics. I remember my lifelong-democrat-voting Uncle Wally, rest his soul, demanding of me, visibly frustrated with his face growing flush, “What is the matter with your Dad?? Doesn’t he know he’s poor??” Obviously, the answer could not be “No, he has no idea, he thinks he’s a gazilionaire.” But here we have a problem with the whole lib mindset, and it must go back aways because Wally was more of an FDR-era kind of lib: If you don’t come to the same conclusion, you must lack comprehension. And here is the part that baffles me, I have to say: As genuinely agitated as the liberal is with the observation that everyone & his dog isn’t leaping onto the bandwagon — genuinely irritated, the complement deserves special emphasis because you can’t fake this — somehow, there is not too much thought that has to be applied to where the point of dispute might be. The first theory is the best theory. Oh, you must not understand that you aren’t a millionaire. Oh, you must not be able to comprehend the number “two thousand.”

It is that last, paraphrased, comment that piques my interest here, specifically the very last raspy inquiry that I placed in the italics. I remember my lifelong-democrat-voting Uncle Wally, rest his soul, demanding of me, visibly frustrated with his face growing flush, “What is the matter with your Dad?? Doesn’t he know he’s poor??” Obviously, the answer could not be “No, he has no idea, he thinks he’s a gazilionaire.” But here we have a problem with the whole lib mindset, and it must go back aways because Wally was more of an FDR-era kind of lib: If you don’t come to the same conclusion, you must lack comprehension. And here is the part that baffles me, I have to say: As genuinely agitated as the liberal is with the observation that everyone & his dog isn’t leaping onto the bandwagon — genuinely irritated, the complement deserves special emphasis because you can’t fake this — somehow, there is not too much thought that has to be applied to where the point of dispute might be. The first theory is the best theory. Oh, you must not understand that you aren’t a millionaire. Oh, you must not be able to comprehend the number “two thousand.”

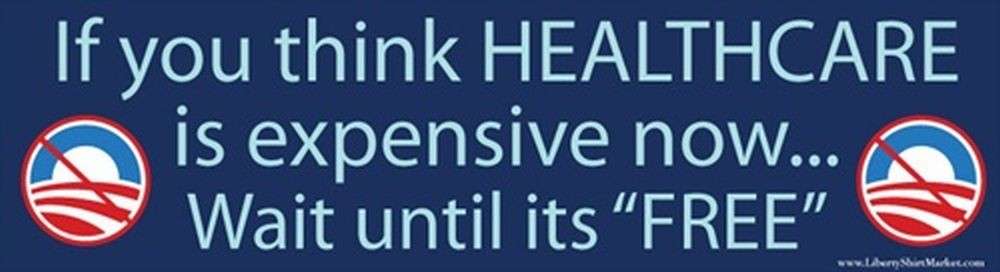

The entire perspective is diseased. There’s no other word for it. This is all an election is ever about, just groups of people getting together and then whoever is outnumbered is forced to do things to suit the other people who did the outnumbering? That’s the whole point, really? Election time…let’s raid that billfold.

The entire perspective is diseased. There’s no other word for it. This is all an election is ever about, just groups of people getting together and then whoever is outnumbered is forced to do things to suit the other people who did the outnumbering? That’s the whole point, really? Election time…let’s raid that billfold.