How To Motivate Large Numbers of People To Do a Dumb Thing, Without Anyone Associating the Dumb Thing With Your Name Later On

This is an ancient skill, one that has been practiced often and our various societies and cultures have been exceedingly tolerant of it. It is a science unto itself, although very few people in history have had the balls to jot it down, let alone create the written encyclopedic resources to describe it. There haven’t been that many interested in practicing it — although, now, it’s becoming more and more popular — and there aren’t that many who are interested in bolstering some immunity to it.

But sadly, it’s worth writing down now. Whether we like it or not, it would appear this “skill” is to become the lifeblood of our future generations. I see a tomorrow in which, if you can pull this off, you get to live under a roof, reproduce, and eat; if you can’t then you don’t, don’t and don’t. I see a future in which we systematically ostracize, throughout a process that involves many stages, anyone lacking the ability to do this.

So anyone who can’t do it, better learn how.

1. Remember, and Exploit to the Fullest: People in Large Groups Are Not Logical

1. Remember, and Exploit to the Fullest: People in Large Groups Are Not Logical

Once the “brainstorming session” is underway, you need to understand the persons participating aren’t there to produce a good outcome. That would imply that they’re looking out for the collective interest…something humans simply don’t do. No, what they’re there to do is to offer up a cosmetic impression that the outcome was going to be an enormous disaster, and then someone else had the wisdom to put their name on the list of invitees and now the disaster is going to be averted. Their individual participation is going to improve the outcome. That’s a subtly different thing from guaranteeing a good outcome.

Now, think how people can accomplish this. There’s the “Idea Man” who’s going to come up with something; without him, everyone else would be standing around all day going “duh.” There’s the Specialist who can understand how an idea would be implemented, and whether or not it would be possible to do so. There is the Skeptic who shoots ideas down. And there is the guy has some responsibility for the way things turn out — the business owner, the divisional head, the project manager. That a group setting is conducive to good ideas, is a supposition that depends entirely on this guy understanding the intricacies of what’s being suggested, with a sturdy comprehension on par with what is wielded by the Specialist.

He doesn’t have this.

Everyone else’s role devolves into multiple instances of yet another class, the “Question-Generator”; that’s like being the Idea Man except less ambitious. Question-Generators, and Not-My-Meeting-ers, the latter of whom are here on an involuntary basis and they think their participation here is a dumbass idea. They have work they should be doing. But they still have to sell something here: The idea that maybe they shouldn’t be in this meeting, but it’s pretty important to have them participate in all the similar meetings, overall. Maybe. Or not.

They’re using their iPhones to reorder their Netflix movies.

Remember how all of these people learned how to attend meetings. It’s the one thing we are continuously taught how to do, all the way back to kindergarten. What’s the rule: To influence what is decidedly outside of your control — to make other people watch you when you think you can look like you know what you’re doing, and not watch you when you don’t know what you’re doing. That’s what all these people are trying to do. They aren’t really there to decide anything. They’re looking after their individual interests, and the group-decision forum isn’t designed to make use of that, it’s designed to make use of the opposite. It’s designed to make use of a human characteristic that doesn’t really exist.

So to bottom-line it all: As you labor to sell a dumb idea to all these people, just keep in mind it really isn’t that hard. Human nature is on your side. Never forget that.

2. Socially Stigmatize the Opposite of Whatever You Want Done

Use the False Dilemma Fallacy, which means to imply that a black-and-white either-or choice has popped up when this is not really the case. The drawback to using False Dilemma is that it sets you up in a one-sided inimicable relationship with the Idea Man — one-sided, meaning you’re aware that the two of your are now in opposition with each other, although he might not be. Just know, going into it, that once the group recognizes a dilemma and it’s unanimously understood that each of the two options offers an unappealing consequences, the Idea Man will be in like flint with a third option; it’s his nature.

But the Idea Man responds to social stigma, like a cat to a hot stove. Just like anyone else. Your sales pitch is then this: Since each option carries with it a unique plus, and then a minus or a plurality of minuses, you offer that your dumb idea as the only way to guarantee that particular plus and that anyone who would place that plus into jeopardy must be operating from an alternative, and unhelpful, value system.

The only way the Idea Man can hope to triumph against such a strategy, is to lay out some speculation that his new idea should safeguard the plus. Your argument then becomes an easy one of contrasting certainty against uncertainty: “Yes, but we don’t know for sure that a crosswalk would keep kids from getting hit by cars, do we? Unlike some people in the room, I happen to care about that.”

3. Switch Moderation and Extremism with Each Other

It’s a dirty little secret about people: They lack the ability to recognize an extreme idea when they hear about it. Even more helpful to your cause, they also lack the humility needed to confess, even to themselves, that they are lacking in this ability. You’d think it would be so easy because the rules are pretty simple: If an idea relies, in verbiage or in spirit, on the concept of “always” or “never” then it is an extreme idea — if it doesn’t, then it isn’t. Simple, right? Easy? No and no. People get hornswaggled by this all the time. They are so much more open to the power of suggestion than they think they are.

Let’s set it up with a worst case scenario: Removing anything associated with America, including the flag, from an upcoming July 4th picnic. That’s pretty extreme, right? After all, if you can set up a rule that Old Glory can’t be flown at a celebration of Independence Day, it naturally follows that she can’t be flown anywhere else.

So all you do is plant the seeds in peoples’ minds, that allowing the flag to be flown is the extremist position. This stuff works. You talk about how when two people from different backgrounds look at the same thing, it’s natural for them to see two different things…and how important it is to keep that in mind. Talk about wounds that have not yet healed, being sensitive to each others’ concerns, showing tolerance for their beliefs. That’s right, make ripping the flag out of a July 4 picnic the “tolerant” position. Like I said. This stuff works.

Presto. You’ve rewritten the unwritten social code, supposedly chiseled in granite at the dawn of time. It’s not so. If you know what you’re doing, it’s putty in your hands. Thanks to you, when you attend the birthday festivities of a country, it is extreme to fly the flag of that country…or to humbly suggest maybe people should be allowed to fly it. It is moderate to rip them out of the ground, vandalize them, steal them, whatever. Switching moderation and extremism around. It’s a lot easier than most people think.

4. Make a Big Show out of Conceding Points That Don’t Really Mean Anything

Once people see you go through the motions of conceding a point, even if it’s a point that doesn’t mean anything, they start to recognize you as being capable of participating in a reasoned and rational exchange of ideas. It’s been well established now that this lures them into believing in your purity — purity of thought, purity of motive, purity of reason — even if this is the last evidence they ever see of it.

Nowhere is this practiced to greater effect than in the discussion of learning disabilities, particularly the Four A’s of Autism, ADHD, Asperger’s and Allergies. It’s used to fasten whatever label happens to be convenient, onto whatever poor child happens to be under inspection. “I’ll concede that lately there has been an issue with overdiagnosis, especially with regard to ADHD — but I want you to rest assured that we are committed to getting Johnny the help that he needs.” See the twist? Logically, if it’s recognized that there is an overdiagnosis problem, then the next place the conversation should go is an examination of whether Johnny is an example of this overdiagnosis. There’s that “perfect world” again; we don’t live in it! Look what’s happening instead. Before the sentence reaches its end, you’ve twisted everything around and made it into a done-deal that Johnny has ADHD and needs ADHD help! You’ve pretended to be available, honest, curious, open to a meritorious challenge…and yet…in substance, you are not.

The reason this is highly effective is it allows the audience to believe that they’re doing all the hard work of participating in a logical discussion, but then it relieves them of that burden. If there’s one thing that never wears people out, it’s recognition for possessing intellectual fortitude and prowess that they don’t really have. Especially the impatient types. Believe me, if people are sitting in a meeting, nine times out of ten they are extremely impatient.

5. Talk a Great Deal About Everybody “Coming Together to do This”

For this to work properly you need people to be a) stupid; b) distracted; or c) demotivated. Your best option is demotivation, meaning in some way or another you’ve made it a “done deal” that this is going to happen. You’ve already gotten the executive layer of your company to buy into it, or solidified your plan as a majority viewpoint, right-or-wrong. Think of this as the second stage of a rocket sending a satellite into space — it’s not much good for the initial lift-off but it’s great for ratcheting things up from already-happening to now-we’re-cookin’.

The wonderful thing about it is the “this.” Nobody, anywhere, is ever going to ask you what it is! You’d think that would be a primary concern to people. You’d think wrong. There’s something deep down in the psyche that is set alight when people are presented with an opportunity, genuine or phony, to be a part of something big; to become a nearly-insignificant part of the muscle-class but not the decision-making-class. It’s as if the prospect of de-evolving and becoming an ant drone, or bee drone, rekindles some long-dormant childhood fantasy.

Perhaps it’s the notion of retiring, for a little while, from adult responsibilities. To go back to the classroom where, if you simply kept your hand down until the teacher called on someone else, you could achieve a little momentary insignificance and anonymity in the third grade that is forever outside of your grasp as an adult.

What you’re really offering to do, therefore, is to share this advantage you are trying to enjoy…motivating people to do a dumb thing without having your name associated with the dumb thing afterward, when it’s revealed to be dumb. You are, in a sense, creating an Initial Public Offering, inviting investors to climb aboard. Invite your audience to become ants. This works. You will be amazed at how quickly they will grow the feelers and the extra four legs. You’re inviting them to share the “profits” involved in this helpful anonymity. “Together We Can Do This” is code-word for “It’s not gonna be your fault, either.”

Your model should be the Foolish Old Man Who Moved The Mountains. This is why all our proposed solutions to the climate change “problem” have to do with “all” of us doing things that amount to practically nothing. Like unplugging the cell phone when it’s done recharging. It’s all about an assault on the individual. If there was some magical button that would somehow stop whatever climate change threat exists — stop it right in its tracks, in the blink of an eye — and it fell upon some individual to push the button, like King Arthur pulling a sword from a stone…nobody would push the button. The appeal lies in doing meaningless, empty things, things that amount to carrying a bucket of dirt away from a mountain, things that have a perceptible effect if & only if millions of peers do the same thing.

6. Use Sixth-Grade-Math While Ignoring Third-Grade Standards of Reason

6. Use Sixth-Grade-Math While Ignoring Third-Grade Standards of Reason

As noted before, people are enamored of recognition for intellectual qualities they don’t really have, especially when they are impatient.

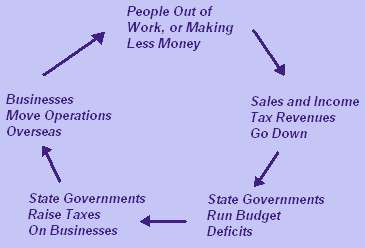

The most frequent example of this tactic, by far, is with regard to tax hikes. Revenue forecasts, budget deficits in dollar amounts, expense increases over the previous year and revenue shortfalls over the previous year — they’re all tossed out as if people are really paying attention to such things. But they aren’t. If people want to get a feeling for how desperate the problem is, they just take a reading of how often they’re hearing about the problem. They don’t subtract or multiply anything. All these numbers, factual as they may be, are simply window dressing.

The logic that is offered is so twisted, an elementary school student should be able to identify where it’s gone wrong: It’s the “Where else is the money going to come from?” argument. Doing nothing is not an option; it’s unthinkable to cut any programs because every program has a defender; the budget deficit is quite serious, we can’t borrow, so we’ll have to raise taxes. Simply asking the question “How did we get here?” plainly illuminates the point that this is the wrong way to go.

But people fall for it time after time, because they’ve been given these “hard” numbers and think they’re qualified to say — yup, raise the taxes, that’s the only option left for us. Better do it sooner rather than later.

7. Find Out What People Are Missing

Once you’ve demonstrated a connection between your concerns and the concerns of your audience, you’ll find people are quite forgiving when confronted by disconnected, trashy logic. So don’t be afraid to turn your dumb idea into a solution-in-search-of-a-problem. Dumb ideas get sold that way pretty much all the time.

Once again: What you are doing is not putting together a meritorious argument; instead, what you’re doing is dispelling the requirement for you to put together a meritorious argument. It would be highly difficult to assemble a meritorious argument that a weak economy will recover through an ambitious “stimulus” program financed through record-setting debt and draconian tax increases against the most productive citizens. Or that the unemployment rate will go down when the minimum wage goes up. Or that when we activate a “disarmament” treaty with a belligerent foreign power, things will work out okay because there’s just no way our former enemy would stockpile some secret weapons and fail to tell us about them.

None of those things make any sense, but they’ve been sold over and over again, quite successfully, through a suggestion that the plan is substantially conducive to the declared goal. Once that suggestion is planted, people don’t check it out to see if it makes sense. They think they did, but they didn’t.

8. Accuse Your Audience Falsely; Make Sure They’re Innocent

A reckless and cockeyed accusation is more potent against a solid personal reputation than most people think. So think twice before abandoning the idea of accusing man known to be honest, of lying; or a man known for his stellar integrity, of cheating; or a man known for his fidelity, of treachery. This might prove quite effective after all.

In a perfect world, when you say to someone “I think you’re (insert something they couldn’t possibly be doing, or something grossly out of harmony with their demonstrated character qualities & defects)” you would be making a self-incriminating comment against your powers of observation and inference. You’d be demonstrating your delusions, your paranoia, and holding yourself out as someone who’s mental instabilities disqualify him from ever making an important decision about anything.

Real life doesn’t quite work that way, though, especially in group environments. In this Bizarro-world in which we live, when you make an accusation, no matter how nonsensical it may be — the possibility exists that you are simply the first in a long line of people speaking up, who are mastocating away on the same idea. This possibility, however remote, calls into question the target’s social standing; and once a person’s social standing has been placed in jeopardy, logic goes straight out the window.

One word of caution though. This doesn’t work if the person you’re accusing is actually guilty, because guilty people generally don’t work very hard to prove themselves innocent once caught. The more typical reaction is “Aw darn, I got caught.” So do your homework first. Follow Thing I Know #273. Make sure the person you’re accusing, is actually innocent.

People will usually spend quite an abundance of energy to prove themselves innocent when falsely accused. If they’re presented with an opportunity to prove themselves innocent, they very seldom question how this would prove their innocence, or even how this is beneficial to their interests, or anybody else’s interests, in any way. The more typical reaction is to do exactly what they’re told — with great gusto.

9. Inject a Snidely Whiplash Into the Situation, Even When There Isn’t One

9. Inject a Snidely Whiplash Into the Situation, Even When There Isn’t One

People have an ingrained instinct to fight each other. They tire quickly of fighting forces of nature, such as the human propensity to spend unearned money, gravity, inertia, or anything of the like. Those things are timeless and inexhaustible. But a human opponent is exhaustible.

You don’t need to offer a possibility of victory, in order to fire up the collective adrenaline of a group of ignoramuses. To simply roll out a communication medium by which the many can convey their dislike of a few, or of a one, is sufficient. In fact, you’ll find it is quite adequate to communicate the message only to that one guy! Letter-writing campaigns — they are nothing more, than this. Just a coordinated attack to blitz some dirty so-and-so with a bunch of boilerplate e-mails…that say nothing more than that the dirty so-and-so is a dirty so-and-so. From a bunch of malcontents who already are on record thinking the dirty so-and-so is a dirty so-and-so. And the dirty so-and-so knows it, and the malcontents are already perfectly aware of that. Purely redundant hustle-and-bustle, in other words. This is far more inspirational to people than you might initially think.

It’s a sad thing about people. If they find someone needs help, they’re moderately aroused into action to make sure that person gets help. But if they catch wind that a dirty rotten so-and-so has gotten away with shenanigans, they feel much more passion about setting things “right.” Overall they’re in a much bigger hurry to inflict pain than to offer aid and assistance where it’s needed.

This is most true of the people who are most energized about conveying the opposite impression. Of all our neighbors, the cruelest and meanest are the ones with all the theatrical “compassion.”

10. Inject a Victim Into It Too

Throughout history, whenever people have banded together to knowingly inflict harm on others, they have always viewed it as a sacrifice toward a noble goal of protecting some third party. This hasn’t always made sense, but the illusion is important. Even a bad illusion. People need to be given some rationale for what they do when they inflict harm and pain. They need a way to say to themselves that they’re achieving a net-positive effect.

This works best with regard to actions that don’t actually hurt someone, but instead, rob them of authority that should be rightfully theirs. Example: Should the city council dictate to a restaurant owner that his omelettes should cost six dollars instead of eight? No, that’s ridiculous. You’d have a lot of trouble getting support for a dumb idea like that one. But — offer up the same idea, with some portrayals of people who can only afford six dollars for an omelette, and the world is yours. Single mothers who don’t have eight dollars for an omelette. Kids who aren’t getting their omelettes.

You’d have the restaurant owner stretched out on a scaffold before lunchtime.

Everyone loves an underdog. And by “love” I don’t mean really love…I mean “abdicates a sense of logic, common sense and responsibility for the sake of.” That’s what I mean.

Update 9/12/09:

11. Talk to Your Audience’s OFC

For even the most rugged individualist, there is a certain psychological pain involved in going against the expectations of society, and people are far more responsive to pain than they are to logical thought. They don’t like to talk about it anymore than they like to talk about their alimentary processes, but like all the features of the alimentary process, it is an unavoidable part of being an evolved organism. People have pain receptors, pain transmitters, and the primitive thought regulation processes to orchestrate behavior in such a way that the pain is stopped or prevented.

Most people will support a falsehood that they know beyond any doubt really is a falsehood, if there is a social expectation for them to do so. This was all pointed out in Item #2 on this list, “socially stigmatize the opposite of what it is you want done.” What you’re doing here, is providing an on-ramp to that. Make an example out of someone flouting the social taboo you’re trying to set up, by pointing out a truth inconvenient to what you are trying to sell. Then offer the suggestion that, since that person is infracting a social order of some kind, anyone who agrees with him must be guilty of the same transgression. You’re engaging here in a fallacy of post hoc ergo proctor hoc. Think of this method as the bastard love child of Item #2 on this list, and Dolphin Logic.

This is a sophisticated technique, easily deployed against smart people. Smart people have special weaknesses: If they’ve been smarter than the average for a long time, and they’ve gotten social feedback about this, odds are they’ve taken some of that surplus energy they’re fortunate enough to enjoy and implemented some of it for the purpose of fulfilling the more subtle expectations our culture has made of them. They relished being told they were as sophisticated as sixteen-year-olds when they were twelve, as twelve-year-olds when they were eight, and so on. So when you socially stigmatize the opposite of what you want done, you’re offering a threat; here, you’re offering a reward. Even more effective than that, you’re offering the continuation of a reward. If you’re successful, all thinking that comes later is routed through the brain’s Orbito-Frontal Cortex, or OFC, the region of matter responsible for figuring out what people “should” do before they have time to weigh logical consequences and alternatives. Once you’ve routed thoughts around that troublesome other part of the brain that actually figures things out, it’s a simple matter to sell the customer whatever silly nonsense you want to peddle. You’ll have them eating out of your hand.

12. Sell the Sizzle, Not the Steak

Pretend you’re talking about truth versus falsehood, and then drone on at length about the hopes you have for what you want to sell — nevermind how far these hopes depart from reality — and the fears you have about the alternative(s). And, again, don’t trouble yourself about how far those fears depart from reality.

The wonderful thing about this technique is that you get to call your opponents liars, but they can’t really call you a liar because you’re talking about things in your head, and deep down everyone realizes this. But they don’t carry that realization forward to the logical conclusion about what you’re saying, that it is at best weightless and meaningless and at worst just a huge old crock of bullshit.

The same goes for your slander about the ideas you’re trying to put down. Your slander can’t be proven because the truth of what you’re saying cannot be refuted. If you say one of your political enemies eats babies, you’ve put the opposition in the position of trying to prove a negative. If they do prove the negative, your position then morphs into one that your opponent hasn’t eaten a baby yet.

The negative side of this is, simply, Borking:

Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is — and is often the only — protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy…