Dad pointed out to me one time where he was born, now ninety-two years ago. If the house still existed, it would be at a spot under the entrance ramp to I-5, 48°44’36.5″N 122°28’03.5″W. This past Friday evening, he closed out that existence. The spot where he took his final breath wasn’t quite there, but close, half a mile away as the crow flies. That house, of course, still stands. Grandpa paid cash for it in the later Depression years, and that’s where my brother and I spent our formative years, like our father before us. The U.S. Census records that he was living there by age eight, in 1940.

So. Born down there by the neighborhood park; moved up onto the hill a few years later, where he would eventually kick the bucket. Just two or three thousand feet. A little bit of globetrotting, state-line crossing, family-making in the middle of it. Eight years shy of a full century.

You can achieve greater stability than that, in your life. It’s conceivably possible. But you won’t beat this by much.

This was the fulfillment of my brother’s life-chapter, which he began a handful of years ago. “Going to make sure Dad leaves here feet first, and not have to go to some crummy rest home. It would kill him.” Well, mission accomplished. They are both to be commended.

Dad was the middle of five children, final survivor of the clan. He enjoyed the simple pleasures of life. He loved salmon, for Grandpa Freeberg was an avid fisherman; lamb, on occasion; and “pot roast” — beef chuck, especially the way Mom cooked it on Sundays. For special occasions when I visited the family homestead, like for birthdays, this would occasionally cause disappointment as I tried in vain to embiggen his horizons. “It’s wasted on me,” he explained. Eventually I would figure this out and stop trying, but he did appreciate the better wines now and then. His other passions were cars. He achieved considerable expertise working on cars, and honing his craft as the years went by and the cars became more sophisticated. There are, and have always been, huge stacks of Motor Trend and Car & Driver magazines at the Freeberg homestead.

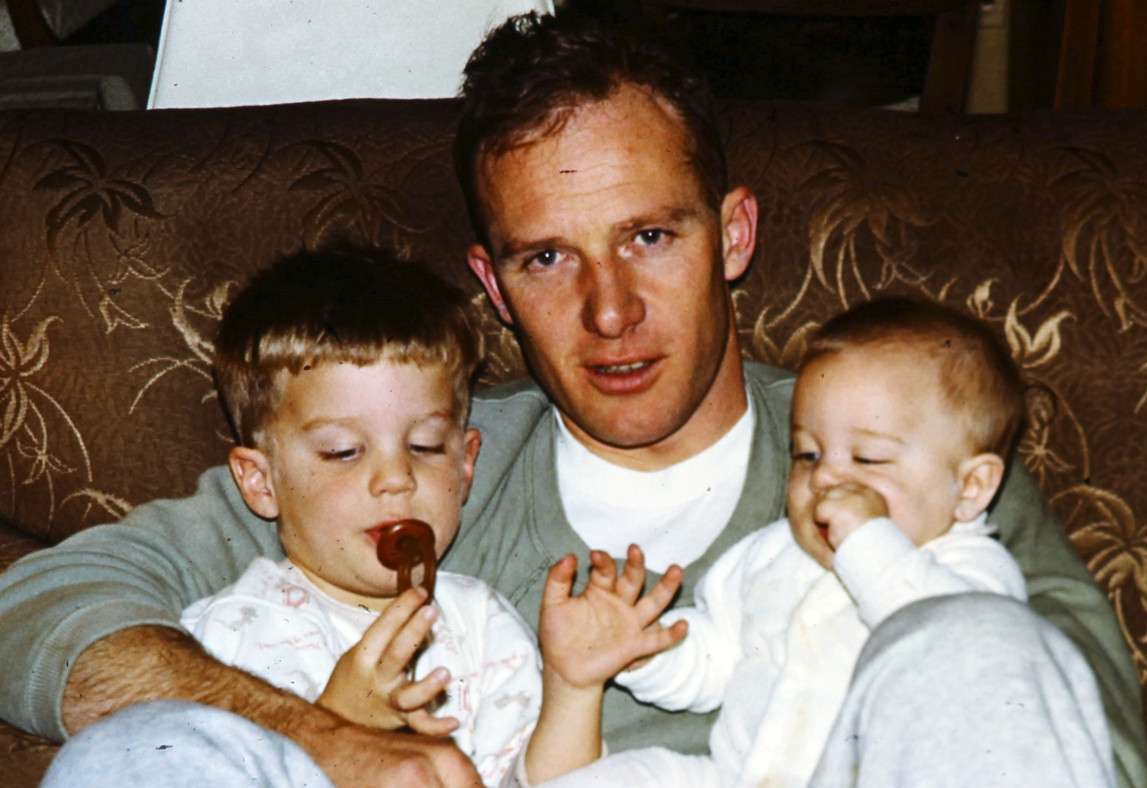

For the yawning gap between his cultural preferences and mine, I always liked to sum it up thusly: The Great Depression ruined him for good, and Europe ruined him some more. The date of his marriage to Mom was August 15, 1954, two days past his twenty-third birthday. Within just a handful of years about that time he achieved maturity, a teacher’s certificate, became a married man and off they went to Europe. They bounced around there for a handful of years. France, Germany, Italy and some others. He called Mom the string to his balloon, and this was a metaphor that worked well with his impulsive, pie-in-the-sky ideas, and her beneficial grounding effect.  The kids — me and him, not in that order — were her idea. She had to work him over for just short of a decade.

The kids — me and him, not in that order — were her idea. She had to work him over for just short of a decade.

Mom was the afterthought in a family that was hit hard by the Depression. There was a cultural gap there, too. You might say they were more into material success than my Dad was, and his economic class was a disappointment to them. His sense of priorities caused further conflict. But we kids came along so late in the game, that everyone had started to behave with grace and maturity, to bury the conflict and act like adults. And so our immediate family remained financially strapped, and uniquely so, but we didn’t know. Like the “Alabama” song says: We didn’t know the times were lean, ’round our house the grass was green.

Dad’s greatest sacrifice for the good of the family, came when he earned his degree at Arizona State University. It was quite the ordeal. The move from Washington State down to Tempe took place before my earliest memory, around the time I was 2-3 years old. So my earliest memories are of palm trees, flat suburbs, lots of desert. This was when life was simple, and in its own way, desirable. Men were men. Working on your car, in the driveway, stripping it down to the frame and pulling the engine out with a cherry-picker — these were the norm. Birthdays were celebrated on kiddie tables in the back yard. That tiny house didn’t have a swimming pool; today it does. We made liberal use of the neighbor’s pool when it got intolerably hot, which was often. Star Trek had just been cancelled but was in syndication. Dad “hated” the show, but was always in a hurry to get home from work before six, the opening credits for the “stupid” show. Yes those famous, famous opening credits, all the Star Trek fans have seen ’em. William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, to boldly go where no man has gone before…

Life events intruded on the degree. We had to move to that boyhood home in Washington State, in 1972, and then Dad went back by himself to finish things. It must have been like a slug crawling on salt. By this time, he was a family man through and through, but he toiled away hundreds of miles from us in his crappy little apartment, in the Phoenix summer heat toiling over the typewriter, in his underwear under a half-ass swamp cooler. But, he stuck it out and earned his Ph.D., thus becoming “Dr. Dad.” How much of a career did he manage to build on this? More than nothing, but less than what he’d hoped, I think.

It was forty years following these events, spring of 2014, I took my son back to where it all happened. I was impressed with how much the house…shrunk. No, we didn’t impose on the family living there, we just looked at it from the outside. I was 47 that spring and the last I’d seen of it, I was just 6. Everything was shorter, the driveway was narrower, and the cement walls separating backyards from alleyways, which seemed to pierce the very sky before, were practically mere decorations.

The walk to my old Kindergarten school was a different story. We retraced it, just for fun. Quite a hike for a five-year-old. And in the 1970’s we were on the dawning of the age of serial killings and kidnappings. It just goes to show what a risk-averse, foam-rubber-cushioned crash-helmet society we’ve become. Back then, kids went wherever. When the street lights come on, get your butt home for supper or it’ll get beat. That’s how we did it.

A helmet was for when you pretended to be a pro football player. Nobody had knee pads. If you jumped off the wrong thing and landed the wrong way, you took your road rash to go in and see your Mom and she’d apply a disinfectant that stung like hell. Then, back outside you went.

The move from Arizona back to Washington State, that is the first one with the whole family — that was a herculean effort that sapped the energy of all involved, until there was nothing left. Mom found it unforgettable, and in all the wrong ways. She drove the moving truck and Dad followed along in the family sedan. They/we must have bisected the trip making it two days and one night. There are no details that survive the stretch of time, verbal or written. My parents were beat. My brother and I…weren’t quite. It was quite the adventure for us, watching teevee shows in a Motel 6, in what could have been Southern Oregon, but more likely was Yreka or Weed. Listening to the druggies outside, what sounded to our young ears like a witch’s cackle followed by a huge explosion. Mom and Dad slept right through it, their bodies draped on top of the covers, face-up, snoring. So my brother made sure to wake them up and tell them all about it, or try to anyway. Heh. Kids are adorable.

The move from Arizona back to Washington State, that is the first one with the whole family — that was a herculean effort that sapped the energy of all involved, until there was nothing left. Mom found it unforgettable, and in all the wrong ways. She drove the moving truck and Dad followed along in the family sedan. They/we must have bisected the trip making it two days and one night. There are no details that survive the stretch of time, verbal or written. My parents were beat. My brother and I…weren’t quite. It was quite the adventure for us, watching teevee shows in a Motel 6, in what could have been Southern Oregon, but more likely was Yreka or Weed. Listening to the druggies outside, what sounded to our young ears like a witch’s cackle followed by a huge explosion. Mom and Dad slept right through it, their bodies draped on top of the covers, face-up, snoring. So my brother made sure to wake them up and tell them all about it, or try to anyway. Heh. Kids are adorable.

Our consideration or lack thereof made very little difference to Mom. At the end of the move she announced she was done moving, anywhere, and for good. She was going to leave that house feet-first. And that’s exactly what she did. The same house Dad left, the same way, thirty years apart, with her time coming February 27, 1993. Same time of day, or within an hour of it, interestingly enough. Mom on a Saturday, Dad on a Friday.

Anyway, forgive the bouncing-around in the timeline; back to the fall of 1972. Thus ensconced in Dad’s boyhood home for the remainder of childhood, my brother and I picked up new routines fitting our tender age and rotated in new routines as we advanced. Dad had a fetish for farm life which was at odds with our suburban location, but the spread is half an acre and there are “chores” aplenty. He parceled them out to make sure we were busy, which caused some rancor as we approached teenage years and could start to see the priority was questionable. To us, at times, it looked a bit like “Dig a hole, dig another hole, take the dirt from that hole and put it in the first hole, now dig the first hole again and put the dirt in the second hole…” So we learned something that could be called a work ethic. The household income continued to dwindle, and when things didn’t go well for Dad, Mom helped. We kids helped too. We delivered for the local newspaper, yes kids could do that back then. I started a lawncare “business,” with Dad’s “encouragement.” My parents were both genuinely thrilled with my customer list, which secretly worried me. Really? This changes our financial prospects? Like for the whole household? A snot-nosed kid mowing lawns?

These were all team/family efforts, of a sort. Dad and I spent much summertime time together cutting those lawns. It must have been a humbling experience for him: Closing in on fifty, when most men should be prospering, cutting lawns with his son to make ends meet. But Dad went at it, as cheerful as ever, like it was just another chore to be done in our own backyard and he got his batteries recharged doing chores. In fact the only time I saw his disposition change was when I followed him as we cut a double-swath, a lawnmower under the command of each of us, and in a moment’s inattention nearly ran over his foot.

To his credit, he played the extrovert, always. I say “played”; I slowly caught on to the reality that he was an introvert, conquering a fear. He was always a shy man deep down inside. But I remember the dinner parties with our neighbors on the street. The dining room still exists and offers an impressive view of Mt. Baker and all the vast acreage between mountain and house, so you can see why this would be the choice meeting spot for the neighborhood. This is something I’ve tried to emulate in my role as head of household, the informal congregation, meeting-of-minds, re-enacting the birth of civilization. Back then we could talk politics without attacking each other’s character. We vote for Ford, you vote for Carter, but we’re still friends. Funny, huh? And they’d talk over what causes what, the values that lead to decisions and preferences, and it would drag on until one in the morning. Nobody got bored.

But Dad didn’t turn activist until a developer showed up in town to build a shopping mall. This ignited his passions. He was on the Luddite side, the “But this is where I grew up” side. It was a losing battle. From that point onward, purchase-planning was consistently done with a footnote, express or implied: “Not at Bellis Fair.” Soon after the battle was lost and the permits were approved and the cement poured, this was easy. But lately, you go visit Bellingham and you just try it. The mall is right there, in your face, sprawling across acre after acre and it’s where the business is done. Can’t stop progress.

My brother joined the Marine Corps. Mom was furious. It was among the first, if not the first, of his signatures applied to paper that carried legal force as he’d reached majority age. She made sure to point this out to him. She went full Sonny Corleone on his decision, but it was too late, and his decision. It was after he completed boot camp that the U.S. Marine barracks in Lebanon were struck by two truck bombs, October 23, 1983, with a death toll of over 300. Naturally, my parents’ faith was shaken. But, my brother was a champion drummer, world-class, and wound up in the Commandant’s Own band. Mom’s relief was palpable. “At this point, my son is probably safer than yours,” she would say to the churchgoers expressing their concern and interest. These were turbulent times. She might have been finding a tactful way of saying, I’m more concerned about my other son than that one.

With me a virtual only-child, my brother missing all the local drama, Dad “ruined” Thanksgiving repeatedly. His brother, my Uncle Albin, was a functional schizophrenic. Capable of living independently, but handicapped, on assistance, occupying public housing. Dad showed his Christian good feelings by shuffling off to the other side of town, in Fairhaven, to the subsidized apartments, with me in tow and sometimes doing the driving. It was an ordeal. You approached the locked doors, looked up the apartment occupied by the person you wanted to see, and you “buzzed” them so they’d press a button granting you access. Albin didn’t have a phone. So…we’d stand there like jackasses pounding on the door hoping a kindly denizen would get curious enough to bend the rules. Once in the lobby, we’d express our profound thanks and head up to see Albin.

Albin had a memory for this ritual, much like a house cat’s: None. “Oh, there you are interrupting my nap again” the cat might say. Whaddya want? And Dad would explain, and re-explain, every year, that it was Thanksgiving and we were there to see to it he didn’t spend it alone. Albin’s interest piqued with the description of the food. Oh, well that sounds good. And then back we’d go. After the meal, he’d slump in front of the teevee while we’d clear off the dishes…then he’d slip quietly out the door and walk home.

Dad never gave up on Albin. He might chuckle good-naturedly at some of this quirky behavior. But he never complained. I complained, occasionally, until I was well acquainted with the futility of it. It looked like just a way to torture me. But I came to realize it wasn’t about torturing me, and it wasn’t really even about educating me, although there was some faint hope there. He was being a true, good-hearted, decent Christian. Maybe making up for some other behavior not so desirable. But I came to realize in the ensuing years that whatever the motivation, it was not to gussy up his community image or preen. It was just good old-fashioned kindness, to a recipient who could not do anything to repay. Now, as then, the world could certainly use more of that.

Opportunity came in the direction of my Mom, who managed to fill out her half of a partnership offering word processing and secretarial services in downtown Bellingham. After a little while in that situation she bought out the business and grew it into a charming retail establishment, The Paper Crunch. This soon became an all-consuming family affair, and I could write an entire tome about just that. But, it hasn’t got a lot to do with Dad. As I was getting my adult life started and leaving home, that made my parents empty-nesters and the business was giving Mom a renewed sense of purpose. It was nice to see her thriving and making use of this new income to support our/her family. But it must have been crushing to Dad, having this final verdict delivered that his Psychology degree wasn’t, after all, paying the bills. And I got the impression after awhile that one of the business’ key reasons for existing was to keep me from leaving town.

So, of course, I left town. Seattle beckoned.

After a few years of this new configuration, with both sons going through bumps in the road getting our respective lives started and having our parallel madcap misadventures with women and marriages and divorces; in the fall of 1991 I was living in Everett, working for a software startup down in Sea Tac. I was summoned back to Bellingham by can’t-remember-what, phone call or something. Mom and Dad had established a new routine, filling their empty-nester lives with participation in clubs to stimulate the mind and make new friends, potentially establish business contacts. One of these was Toastmasters. Mom was honing her skills at delivering speeches to audiences, an activity at which she’d always been a little skittish. There was nervousness and there was stuttering. Well, one day the stuttering was worse than usual and she realized she was having difficulty getting the words to her mouth. It felt to her like a physical problem so she had decided to go in and get scanned.

They found something.

The tumor was cancerous. And, as the months went by and she started to outlive the various diagnoses, it emerged that she wasn’t going to outlive all of them. This was entirely inoperable. There was, I recall, a brief flirtation with chemo and some resulting hair loss, but there never was too much optimism about this. A year into it, it was time to send her home for good and make her comfortable. By this time I’d accepted a job offer in Detroit, and I could write another lengthy tome about the conflict that arose around that, and Mom’s stalwart way of dealing with it. Dad just didn’t want me to go. It was a weird thing our parents had happening; Mom was the Dad, and Dad was the Mom. String, balloon.

From Detroit, I was transferred to California, partly as a mercy act because of this family situation and partly in response to my performance which was distracted and ultimately disappointing. I’ve lived here ever since. At this point Mom was months away from death, perhaps just a few weeks, so I did what I could to visit more frequently. Her powers of speech continued to elude her as the tumor grew. The last time I was ever to see her conscious, we all knew it. It was that final Christmas visit. I remember Dad was trying to distract, and trying to keep me from leaving, asking some meaningless question about the television and how it worked. Trying to make me feel needed, trying to keep me from leaving, ever. And then this weird pall fell over the room, like someone had swung a perfume censer. Nobody said anything for a few moments, and then Mom wordlessly motioned for me to come over and say goodbye. We embraced. She couldn’t say anything. She didn’t need to say. Her message was clear. Get out of here, go kick ass. Don’t look back.

The next time I came up from California, it was mid-February. She was in her coma. I remember my flight arrangements had been screwed up, and it took me around 24 hours to fly the 700 miles or so. I was disgusted with the whole process. For the funeral, I drove. At the graveside service, Dad’s hands visibly trembled as he lowered the container of Mom’s ashes into the ground. We the sons were 29 and 26, and we were both cringing, imagining the carton tumbling out of his enfeebled hands and spewing ashes and bone fragments. It didn’t quite happen. Dad was trying to keep a brave front, a cheerful one, but we all knew his whole life had been up-ended.

Even in times as dark as these, he could be funny. I remember him nudging me as we were sitting at the service. He must have seen I was lost in thought, and maybe could use a chuckle. He whispered, “Mom always called this my funeral suit.” And from the various dusty pockets he started to pick out…the program for Grandpa’s funeral back in ’75, Grandma’s funeral ten years afterward, Aunt Thyra’s funeral, his friend T.J. Pirung’s funeral…etc. Dark humor for dark times. No, Dad was not a “suit” person. He just had the one.

But the rest of the time, after that, he was morose. Without a woman around, the family started to disintegrate. Dad wasn’t up to living on his own. He married Mom’s hospice caretaker, Sharon, which caused some rifts with us, his sons. But, at least the old man wasn’t completely miserable. On the other hand, Sharon was disabled, and some of her problems were mental. So he was taking care of her. Over time though, he lost his cognitive abilities and it began to emerge that her job was to take care of him. It was a bit unclear. Throughout the years, this turned into yet more drama as the reality set in to everyone, the two of them combined could barely clear the bar in the capacity to live independently.

When I married Simone just after Christmas in 2012, we flew Dad and Sharon down and put them up in a hotel downtown. Dad declined the offer at first, then went off by himself to do some thinking and realized the narrative was setting in that I wasn’t part of the family anymore. And so he reconsidered, and they arrived for the wedding. This was rather awkward. We spent much of the time we were supposed to be spending preparing for the ceremony, chasing after things. So-and-so left such-and-such at the whatever. Laptops, gloves, power cords. Dad apologized when it was all over and he arrived back home, conceding “we’re out of practice with traveling.” And, thanks for sending along the laptop that he’d forgotten at the security station boarding his return flight.

In 2014 after we bought the house, they visited again. This time driving down by car. This caused great consternation all-around, since he’d already had some episodes driving on long distance trips. He was 83 by now. He had visited us once before, in our palatial apartments, losing track of time and showing up well after dark. Lots of families have to go through this; you wonder when it’s time to take Grandpa’s keys away, and you don’t want to do it because once that edifice of independence is removed, you know the subsequent decline is going to be devastating, quick and tragic. But he’d already fallen asleep at the wheel one time, and with my kid in the car. That provoked an intense confrontation, and one could tell acute embarrassment on his part. We never permitted that again, which caused him anguish, but he knew the reason why. Old age can be cruel.

But I have to credit Dad with balls. He did visit us. Few other family members have.

Thankfully, the round-trip proceeded without incident. He was going to roll through and continue onward to repeat my visit to the old family homestead in Tempe, but ultimately recognized his limitations and headed home again.

Those who protested that his life was plenty complicated enough without travel, were correct. This childhood home of his has a linear driveway, which can store maybe up to eight cars depending on the models and styles, but only one can exit without disrupting the others. While Dad struggled to recover his auto-mechanic acumen in his advanced age, the other cars languished as projects. According to the letter of the law in Bellingham, that’s illegal. This created a confrontation with the local police department. Someone tattled on him, and he got cited. But then there was someone else, at City Hall, who felt sorry for him. And it seems a compromise was reached where he’d satisfy the letter, albeit not the spirit, of the ordinance by covering the derelicts with ugly tarps.

The hearing aids became — there’s no other word to adequately describe it — a shitstorm. We always thirsted for more information about this, suspecting he wasn’t receiving the best care because his equipment kept falling out of his ears when he chewed his food. That’s not supposed to happen. The equipment prescribed racked up higher and higher price tags, reaching into the thousands. And then they’d fall out of his head, and he’d find them later in the gravel of the driveway.

My brother, at some point, had enough. He was between business engagements and between marriages, and made the decree that “The Marines Have Landed” and proceeded to move in and put everything in order. Dad found some weird ways to protest this. The Platoon Of One would clean up the basement stairs so it wouldn’t be so easy to trip on them. Then he would, in exasperation, e-mail me some pictures of the steps “fucked up again” when the Old Man dumped some more debris on them, very much like a dog piddling on a tree to mark his territory. Dad tripped, in the middle of the night, probably on a stack of magazines, and broke his hip. We were about to visit and take everyone to the new Star Wars movie. Dad’s enthusiasm for that part of the agenda was always lukewarm at best. But he chuckled when I told him “If you really didn’t want to go see it, all you had to do was say so.”

Equipped with a cane for his daily wanderings about the family property, he misjudged a landing, slipped, and rolled down a hill breaking some ribs. This was a year or two after the broken-hip debacle. He received a stern talking-to and resolved to mend his ways, which apparently he did.

This is how it was for the last, approximately, twenty years or so of his life. I shouldn’t assemble a complete chronology, even at a high summary level, because although it’s loaded with some good suspense and some things that make the reader go “OMG WTF”…you could describe most nonagenarians, and their experiences living independently, much the same way. Always the family is wondering what to do. The family is eyebrows-deep in passionate arguments about “Do something” and “No don’t do that”…with solid points to be made on both sides.

I’m going through the litany, here, to illustrate the challenge of proper remembrance. It’s tempting to think of Dad as this headache, and it’s especially tempting for the people who bore the brunt. But that’s wrong. He lived seven decades before all that happened. This is the man who sweated away in his underwear, in sparse, lonely Phoenix, probably in the most miserable summer of his entire life, and for us. I choose to remember that.

Dad had a lifelong fascination with the British sedan, the Rover, but unfortunately he waited until the winter of his life to figure out what was the deal with those rubber motor mounts. The Rover is powered by a longitudinally mounted inline-four liquid cooled engine, usually 2000cc displacement.

This part is sad: He put it on his bucket list to figure out why the inline-four needed the flexible motor mounts, and then when running proceeded to buckle and jostle back and forth, whereas a V-8 or flat-opposed six just sat there even if you red-lined it. And his youngest son had the answer. So, let the prying begin.

Patience, patience, patience.

I quickly learned this was a matter of what you might call “linkage.” Like many an old person, Dad would come up against a concept that eluded him, try to conquer it, and failing that become lost. This is, I think, why there’s such a durable connection between hearing loss and dementia, it’s an issue of isolation. I found I could restore the linkage by retreating back a few steps, into complex technical details he had already managed to conquer back in his youth.

Two cylinders are up when the other two are down. Why is this not balanced? Why the shaky-shaky? That’s the question.

They’re not secondarily-balanced because the piston doesn’t approach top dead center at the same speed as bottom dead center.

What? Why?

The inline four is primary-balanced because two are up when two are down. Remember how the crankshaft looks. Piston one, toward the front, is up when piston four is up; two and three are down. This drives a four-stroke pattern, there are 720 degrees in four strokes, 720 divided by four is 180 so that’s why the crankshaft looks that way. The firing order is one, three, four, two.

Yes! And with that, his eyes had a new light behind them, and he’d come alive. He’d re-engage.

Okay. We’ve restored. Deep breath…

Now, imagine the crankshaft turning another 90 degrees. One and four have retreated from the top, two and three have progressed from the bottom. All four pistons are at exactly the same height, but that falls short of the true halfway point. They’re slightly below that.

Uh…

Means the pistons are moving faster, up and down, when they’re in the upper half of a cycle than they are in the lower half of the cycle. All four.

Huh?

And we’d go around and around about this. He had the brain cells to understand the concepts. But he didn’t have the cells that were needed to grasp the new ideas and put it all together. One cocktail napkin sketch after another emerged from under my pen. I tried the Pythagorean Theorem, which Dad understood well. Putting it all together should have been a snap. But somehow he couldn’t quite manage.

We often caught him selectively failing to understand things he didn’t want to understand. This was not one of those things. He had racked up perhaps hundreds of hours working on Rovers, watching the inline-four rock back and forth in those rubber motor mounts like a galloping pony. He really wanted to know. He was able to almost grasp it, to comprehend that pistons were counterbalancing other pistons that were moving at slightly different speeds. But he could progress no further from that point, and he forgot that much within minutes.

For his 90th birthday, August of 2021, we journeyed on what today I consider to be the “Can’t Go Home Again” trip. We stayed in a hotel down in Fairhaven for five or six days, and without going into details, I’ll just summarize that it wasn’t a good idea. It started out fine. I got Dad a Ka-Bar. I went to our local sportsman’s warehouse, found the one that would allow for engraving, and managed to get hold of the grumpiest guy in the store to unlock it for me. But the clerk came alive when I told him it was for Dad’s 90th.

Shopping for this stuff is fun. People love this stuff. We don’t all live to ninety, and not everybody wants to do so, but if someone manages to get it done it’s a real blessing. All these old duffers have a story to tell about drinking exactly so-much of this kind of beverage every night for the last zillion years; with Dad it was Burgundy. One glass of the cheap stuff in the gallon jug, and a swimming ritual at the local YMCA, that carried him to ninety years and — cognitive issues aside — looking in fine shape to crack a hundred.

Shopping for this stuff is fun. People love this stuff. We don’t all live to ninety, and not everybody wants to do so, but if someone manages to get it done it’s a real blessing. All these old duffers have a story to tell about drinking exactly so-much of this kind of beverage every night for the last zillion years; with Dad it was Burgundy. One glass of the cheap stuff in the gallon jug, and a swimming ritual at the local YMCA, that carried him to ninety years and — cognitive issues aside — looking in fine shape to crack a hundred.

For an engraver open on a Saturday, we had to drive to Stockton. “Not A Kid Anymore,” I put on one side.

When it came time for Dad to open it, it took him four minutes. You always save the wrapping paper for next year, you know. We have the whole thing on video. He got the humor, and resolved to display the knife on its platform over the fireplace. But he was also impressed with its destructive potential. “Nobody better mess with me,” he said.

Things weren’t going terribly well with the rest of the visit, though. There was conflict. I shouldn’t go into details because there’s always a possibility for reconciliation, but I could see our family was lacking in the harmony that prevailed when Mom was alive. Although Dad wanted me there, a little of me went a long way with everybody else. Or, vice-versa. Bellingham required a much longer break from me, and the feeling was mutual. Dad’s sense of time was, mercifully, shot. At this point he didn’t know what month it was, and when he took naps and woke up in the evening, it was impossible to convince him it wasn’t morning. He also didn’t know how to conduct himself around people; didn’t know how to make the most of a rare visit. He tended to treat people like furniture, as my brother put it. He liked having the people there. But didn’t interact with them very much or at all.

It all pointed to one conclusion: This was a replay of that bittersweet Christmas, the last time I saw Mom alive. Except Mom at the time knew it. Dad had no idea. But I knew I would never see him again.

Exactly six months following that awful trip, I realized there was going to be an obituary, a remembrance, a funeral, or some occasion on which I would require a list. And so I picked up my notebook and enumerated the most important things, out of all the years, my Dad taught me.

Now the time has come to transcribe and put it where others can see it.

Enthusiasm Counts

Children require cheerleaders. This often seems not to be the case. We all know those artistic types who prefer to spend their time alone, honing their craft to fill the hours lacking any human interaction. I’m certainly in that crowd.

“Daddy look what I did.” It starts with that. I’m not saying success is impossible without that. But to have that audience is definitely an advantage, and to go without it is a disadvantage. Dad may understand what the child is doing. Or, he may be faking it. It doesn’t really matter. Later on, much later, the child will provide his own impetus and won’t need outside encouragement quite so keenly. In the tender years, it makes a difference, and no sorry but for a male child, the Mom can’t provide it as well. This is Dad Territory. Why we have ’em. And mine was far above the average at it.

My Dad, when I was just barely figuring out the essentials of things that might possibly interest me later, was my cheerleader. It wasn’t until many more years passed by, that I realized he made a difference.

Eat Slow, Eat Lots

An old Scandinavian custom. There’s something to this. The dinner, like the libation, should be a sort of celebration that the hustle and bustle of the day is in the past. Hopefully, what went unachieved doesn’t really matter, or can wait until tomorrow. The meal should therefore not be rushed. That’s healthy. Of course, when we were growing up television was a big part of the evening, probably much bigger than it should have been. “No television from the dinner table” conflicted with this. But that’s a good argument against television, not against a proper, leisurely-paced meal.

I mentioned that Dad had a routine built around the evening Burgundy. He also had one built around the morning oranges. One fruit, cut up into fourths, then he’d suck out the juices, pulp and all, out of each one. Every. Single. Morning.

You can’t argue with success. The man’s mind deteriorated, but his body lived out nicely throughout the nine decades plus, his alimentary canal intact and avoiding colds & flu more effectively than many of his contemporaries.

Arguing

Dad taught me to argue. He made the mistake of doing this when I was about 10 or 11, and it didn’t take too much of that before he and Mom tried to put things back into the realm of “Because I said so.” But, that’s like transplanting a tree from the backyard back into a small pot. I’m sure the world would work better if more people were taught how to do this, and I think Dad might disagree with that. Or, having it to do over again, would’ve done it when I was 15 to 17. Probably, the place where we’d find common ground is: Dependents shouldn’t argue. Beggars can’t be choosers. Argue to your heart’s content about how & why you should get the things you want, after you secure a source of income and pay for your own stuff. Not before then.

But on the other extreme: There’s this idea out there that if nobody is arguing, nobody is disagreeing. That’s not how it works at all. Social media has made that clear. Spend a few hours on it, and you’ll come away with the same impression others have had countless times: I’m being called an idiot, not quite so much because I am one or because I act like one, but because the other fellow can’t, or won’t, attack my position logically or defend his own. And that sucks.

More people should argue. I mean, properly. More people should learn how.

I see way too many people trying to intimidate others, by asserting such-and-such a thing is “a basic, human right.” Super duper emphatically. Well, sayin’ so don’t make it so. Food, housing, college education, a “living wage.”

Dad had something to say about that. Yes, there are rights. Of course there is such a thing. But what is it? There are those who say, if nobody has to pay for it, then maybe that’s a right but otherwise it isn’t. And then there are those who respond to this with: What about jury trials? They do have a point. Our Constitution guarantees the right to a speedy trial, which compels others to drop what they’re doing and pay attention. And so the government compensates those people. But it also conscripts them. You can plead hardship to kick yourself off the jury. The judge might buy it. He might not. In that situation you don’t have a right to attend to your own business. It gives way to the defendant’s right to a speedy trial. That’s guaranteed. Your own freedom from the ugly business is not. You might very well have to “pay” for this other person’s “right,” and under our system of justice that’s just fine.

Dad had a slightly more sophisticated way of reconciling all this, although it doesn’t address all of the inconsistencies. But it’s as good a litmus test as any.

A right, he said, is something that applies to things you would unquestionably have and be able to keep, if nobody else was around.

Life? Yes. You would have that, in solitude, so that is yours.

Liberty? Absolutely yes.

Happiness? If, under such circumstances you can find it, then you’ve a right to it. So right to the pursuit of. Not quite so much to the happiness itself.

Living wage? College education? Three hots and a cot? Health care?

If those things are provided, or guaranteed, to this person over here…then, that person over there is enslaved. What one person receives without having to earn it, another person has to work for without getting it.

This all seems so elementary. But it’s amazing how many people can’t seem to grasp it.

Did You Learn Anything?

Oh my goodness. This is dark. It made me want to wrap my fingers around his throat and squeeze until…

Because I was a teenager. Teenagers don’t want to admit to their mistakes. And they certainly don’t want to be reminded of them right after they made them. It’s not tactful to ask Wiley Coyote “What did you do wrong?” right after the boulder lands on top of him, right?

After I became a grown-up, my mistakes began to have deeper meaning and more long-lasting consequences. Then I gradually started to understand: Not a one among us is sufficiently fortunate or skilled to get it right all the time. The important thing is, Can you learn?

Since then, more than one person has called me arrogant. I can understand the feeling. They try to get me to admit I was wrong here, there, that other place over there…and I don’t. Seems arrogant. Well, here’s the thing: My everyday life is rather boring and repetitive. I do have my intellect. It doesn’t matter if it’s impressive intellect or not, it’s just there. I have some. I’d have to be quite the daffy idiot to do the same things over and over again as long as I have, and continuing to make mistakes, right?

Talk to me about it when I’m trying something new. Better than even odds, you’ll find the humility that was missing.

And that’s a good thing. Because someone taught me to self-assess, to admit as early as possible that I’d done it wrong, so I can get it right the next go-round. Not meaning to brag, but this is something rather close to a superpower. It makes me rather sorry for people who never get anything wrong.

Life is Like a Roll of Toilet Paper

This is like the opposite. Pure funny. I’m positive he stole it from somewhere, but it nails the truth shut so thoroughly that I have to give Dad +1 for it.

Life is like a roll of toilet paper. When you’ve just barely started on it, it doesn’t seem to be losing anything as you go along. But the closer you get to the end, the faster that sucker spins.

He was closing in on seventy when he said it. Now it’s years later and I’m closing in on sixty.

He bulls-eyed this. Or somebody did.

Good Friends vs. Many Friends

There are variations on this. A lot of people say: Be yourself, don’t change to try to attract more friends.

Dad’s way of putting it was that having good friends is much better than having many friends. When he told me that, I was in school and very far away from being one of the popular kids. It was easy advice to follow. A little while later I had some hard lessons about assessing people’s character, and it cost me. Looking back on it, I could have avoided such unpleasantness if I kept this in mind.

That’s on me. Can’t blame him.

You see? I told you I’m capable of admitting mistakes.

The Purpose of Life Is Not to Be Happy

This sounds cruel. It isn’t. It’s just plain true, and it continues to amaze me how many people don’t get this.

Can you imagine if we successfully purged our existence of everything that caused unhappiness? Disease, famine, war…and then what? Explore the stars? There are a lot of people who lust after this pipe dream of no-war no-starvation no-sickness, but don’t want to take on any heavy lifting with inventing or exploring. Just dangle like a grape, sucking up sunshine and nourishment.

People need to put more thought into this. There’s such a thing as purpose in life, which means there’s such a thing as altogether missing it. No problems and no obligations, would not be a dream. It would be a nightmare.

Identity would go first. And then after that, our sense of community. No one would need anybody, so no one would be needed by anybody.

So don’t despair that we’re not reaching this happiness-plateau, aren’t heading toward it, or that you won’t live to see it. That’s cause for celebration. You put some thought into it, you quickly realize you don’t want that.

When Anything Goes, Ultimately Everything Does

I’m sure he stole this one too, but I’ve tried to Google it and have yet to find success.

But it really doesn’t matter. This is just common sense. We have to have laws, taboos, standards. If we get rid of all of them across the board, and for everybody, then nobody flunks anything. Which sounds great. But that would cut both ways.

You wouldn’t be able to complain about anybody else failing to deliver or to perform. So…they wouldn’t have to deliver or perform. We’d all be left with nothing, save for the donations people make because it tickles their fancy. So there’d be some occasional dancing, singing, and playing musical instruments. But the sewage pipes wouldn’t be cleaned, the cars wouldn’t run, and there’d be no torts or laws.

Again, it continues to surprise me how much energy people put into toiling away for a perfect new world they think would be a dream come true, when it would really be a nightmare.

Am I My Brother’s Keeper?

This is the question Cain asked God, when the latter queried him about the whereabouts of his brother Abel. You’ll recall Cain had murdered Abel in a fit of pique when God accepted the victim’s sacrifice of meat cuts, and refused Cain’s offering of pottage. The blood of Abel cried out to God from the ground, and when God asked Cain where his brother was Cain asked if he was his brother’s keeper.

Cain was marked by God, and doomed to wander, for having committed this first murder. A lot of people think that’s the point of the story.

My Dad always read a great deal of meaning into this question, though. You’ll notice, he said, it was never answered one way or the other.

You see how this all ties together. The late night parties where we broke bread and drank Frangelico with the other families on the block, for no reason, just because we were all capable of making the time; the purpose of life is not to be happy, we have to help each other; and we may not have to account minute to minute where the other person is, but yes we are our brother’s keeper. It all points to the same direction. We may work in silos and we may spend time in silos. But we’re not supposed to live womb-to-tomb that way. We exist alongside each other. We’re supposed to support each other. We’re all brothers.

Delayed Gratification

Of all the things my parents taught me, this is probably the most important out of all of them. Because the other things I might have ultimately figured out for myself — but not this.

A lot of times in life, you have no choice but to take the long view. There are a lot of smart people who go their whole lives never understanding this. Don’t go assuming every little effort you make is a sprint. There are marathons.

Losing the battle to win the war — if you play it right — can be extremely effective. It is a strategic talent. You’re very far ahead in life if you can achieve command of this.

Also, learning the value of delayed gratification can make you much less of a pain in the ass to others.