Blogger friend James Bostwick at Newsblog Central took note of a study done by a bunch of clipboard-carrying, white-coat-propeller-beanie-wearing egghead researchers out in Chicago. I will link now and tease later, because for now I want to talk not so much about the study itself, but the thoughts that came back to me while I was reading about it. Let’s just say for now the subject of the study is human interaction.

The egghead researchers have been nudged by their own research into concluding there are basically two types of people. It gets much more complicated than that, of course, but that is the gist of it. Well, bloggers can also notice there are basically two types of people…and here at the Blog That Nobody Reads, we’ve been doing exactly that. We’ve discussed it at length in a series called — arbitrarily — Yin and Yang. There is little inherent meaning involved in the name “Yin” and there is no more inherent meaning in the name “Yang”…except just this. In classic Taoist philosophy, “Yang” is used to describe energy that is boisterous, jovial, masculine and maybe slightly obnoxious. “Yin” is used to describe diametrically opposed but complimentary energies that are introspective, feminine and dark.

We’ve written eight installments about this. This is the ninth. The eight installments are as follows:

Yin and Yang was posted on February 12 of last year. It is inspired by the budget problems of Porter County, Indiana, which found itself in the red because a computer glitch allowed a home to be assessed at about 3400 times its real value. I made the observation that, since nothing had concretely deteriorated on the income side and nothing had concretely expanded on the disbursement side, you had to have a certain personality type to translate this hiccup into real financial gloom. You had to spend first and ask questions later. That’s what it takes to snowball a simple disappointment, into a disaster. This is not unique to Porter County by any means. But it does show that what county governments tend to do, which is to get all the money spent, can lead to serious problems. And yet they’re going to keep right on doing it this way, because when you reject someone’s expense request, they feel better knowing the money is all gone, than they would if you told them there’s a surplus available but you don’t think their idea merits dipping into it. It’s all about feelings. That’s the point of that installment.

Yin and Yang II was posted on April 9, inspired by a story in the Sacramento News and Review which I found to be highly deceptive. The subject of the story was Michael Morales, who was sentenced to death for beating a girl to death with a claw hammer; more specifically, Charles McGrath, the presiding judge at Morales’ trial. Now, going by the cover, the headline, the sub-headline, and the first couple of paragraphs of the story you are invited to come to the conclusion that Morales is innocent, or at least, that McGrath thinks this may be the case. That’s a virtual lie. McGrath’s objection to Morales’ path, as the killer tumbles through the workings of our legal system, is procedural. I made the observation that there is a certain personality type taken in by this deceptive form of journalism, and that actually, from the perspective of that personality type, the deceipt would probably be immaterial. Again, it’s all about feelings. Also, I hypothesized, in my role as an uneducated layman, about how childhood development might take place in each of us, so that the decision is made regarding which personality we’re going to form.

Yin and Yang III was posted on May 1, and it was inspired by the profile of Marissa Leigh, who is being carefully groomed, no expense spared, to become the next Britney Spears. Now it could very well be that Marissa Leigh is a nice, intelligent girl, and that her mother has the best of intentions. According to the information that has found its way to me, most of which is in the article linked, Marissa Leigh is an intolerable airhead and her mother is a pernicious bitch. It is a mystery to me why, and how, anyone would want to raise their daughter this way. There is a payoff to be realized from the years of what I see as nothing more than child abuse. The payoff makes sense to millions of people, whereas, to millions of other people who think more along the lines of the way I think, the payoff is for all purposes non-existent. I started to delve further into why I believe these two personality types are fundamentally incompatible. When contact is attempted, disharmony is the inevitable result. I have no interest in coming into social contact with people like Marissa Leigh; I know from experience, they have no interest in coming into social contact with people like me.

A week later, on May 8 I posted Yin and Yang IV, inspired by the story of young brides in certain Chinese provinces being forced to cry at their weddings. This highlights something about the “Yang” I’ve been noticing my entire life, albeit consciously only for the last decade or so, maybe less. There is something controlling about them. There has to be. When you want to think a certain thing, which is the paramount goal at any moment of the Yin, other people can think whatever they want to think. But when you want to feel a certain thing, which is what the Yang want to do, your goal is obstructed when someone else feels the opposite. And so you cannot permit this. You want laughing, everyone else must laugh; you want crying, there will be crying dammit. Also in this installment, I repudiated the notion that I was the inventor of the concept of splitting people up, and listed several articles of world literature showing that this is a well-established and ancient fantasy, probably as old as mankind itself.

On June 9, I had watched the “Grapple in the Apple” between Christopher Hitchens and George Galloway, MP, and noted in Yin and Yang V how similar this was to the match-up between Bill O’Reilly and David Letterman five months previous. Both exchanges were “debates” according to the rules of cosmetics, and cosmetics alone. In neither one of these couplings did the combatants address common arbiters, instead, what they did was take turns delivering monologues to chosen population segments. Galloway and Letterman made their pitches to The Yang, who like to feel good, and Hitchens and O’Reilly (with minor exceptions) played to The Yin, who like to think things through logically. The political situation in 21st-century America, in which The Yang barely lose out in one election after another, dictates that logically the two sides should be making arguments quite different from the arguments they are making. I noted that my theory explains this — nothing else does — and examined how the evolutionary forces have driven us to this point, where the two sides are in greater conflict with each other than they have been before.

I wrote up Installment VI on July 8th. It has to do with what we call “leadership,” and what exactly that is. To summarize, there are two kinds of leadership and they could be thought of as wartime leadership and democratic leadership. The former identifies ways to reduce the danger posed by a grave threat, and ultimately to defeat that threat. The latter has to do with synergizing widely-felt sentiments and translating them into actions that affect everybody, hopefully for the better. In the first of those two situations, the handicaps of the Yin mean very little to us, and the danger we face tends to elevate Yin people into positions of power. In the second, we are concerned about not being marginalized, making everything be the way we want them to be. We then tend to choose leaders who show prominent abilities to represent themselves as being like us. These “Yang” leaders, with their weaknesses in separating truth from fiction, come to be valued for their communicative abilities and, again, their handicaps mean very little to us. And so throughout history we see the people who run society, change in their personalities depending on the challenges those societies face at a given time.

By December 3rd, people had begun to write in expressing interest in following The Blog That Nobody Reads in general, and Yin and Yang in particular. I thought it was presumptuous to drag them through those six bloated chapters so I put up the seventh installment which is unofficially referred to as the “Foxworthy Chapter.” It just goes on and on about the things you might do if you are Yin, and the other things you might do if you’re Yang.

On February 24th, our new House Speaker sounded off against Vice President Cheney using a favored mantra of the Yang: “You cannot.” I wrote up the eighth chapter to highlight what her overly-simplistic statement proved, to me, beyond any doubt: Those who awaited the House leadership and the White House to come to some sort of compromise about things, were bound to be disappointed. The two sides cannot be reconciled. They come from different planets.

Before going further, I should note that I’m a blogger and not much more than that. I’m not a psychologist or a neurosurgeon or anthropologist or even a daycare provider. I’m just a 41-year-old guy who’s lived with and worked with people. And I’ve got certain weaknesses in doing that. Ironically, in the realm of dealing with people, weaknesses can be educational. Some folks don’t have weaknesses, and end up not learning anything because they don’t have to learn anything. That’s not me. So you could take what follows as stuff that comes from experience; stuff that, if a time machine were invented, I might be interested in zipping back twenty years and telling myself. That’s all it is.

And because I’ve had those weaknesses, I would think the twenty-year-old me would pay attention. At least, he should.

The thing about Yin and Yang is that it’s just one way of dividing people, out of many. Take a minute or two to think about these. Some of us are men and some of us are women; some are masculine and some are feminine. When you have a plurality of these divisions, and you start testing large numbers of people according to those axes, you run into large and small overlaps. You gather up a hundred men and a hundred women, and there will be a general tendency for men to be more masculine than women, and women to be more feminine. But you should expect to find errors, or more precisely, anomalies. Fifteen to twenty women, perhaps more, will be more masculine than some of the men.

And this goes for everything. Simply put, correlation is not causation. Gather a hundred left-handed people and a hundred right-handed people, and overall there will be a tendency for left-handed people to be more artistic. But it’s almost never an absolute. A hundred people who know how to fold shirts, coupled with a hundred people who do not — you won’t find a hundred men in the don’t-know-how group. Seventy-five, maybe. Probably more than that. But there will be some gals in there. Every trend has a couple of odd birds ducking it.

One additional thing you need to think about with regard to Yin and Yang, is the distinction between knowing how to do something, and having something come naturally to you. Yin and Yang has to do with social skills. Not just what you see when you start to meet large numbers of people, but how those people relate to you, and to each other. Some know how to communicate, some do not. Yin and Yang doesn’t have to do with whether people communicate effectively — it has to do with how. It’s got to do with brain activity.

Because it concerns how people see each other when they do their communicating, it has to do with how they program themselves to do this communicating as they go through life. Yin and Yang, therefore, is unique among these divisional axes. There is no middle-ground here. Divide people into left-handed versus right-handed, and you’ll have ambidextrous people in there. Divide people into masculine and feminine, and you’ll have some folks who are poorly-defined sexually. Divide them into intemperate and patient, and you’ll always have some “five-outta-ten” types.

There can be no middle ground with Yin and Yang. That’s because every year you communicate people in the manner of the Yin, it becomes progressively more difficult for you to ever do it as a Yang — and vice-versa. We become more and more entrenched into whichever half we have chosen for ourselves, just by living life.

To understand how this works, let’s inspect very young children in their formative years, but not the average kids — let’s concentrate on the very best and brightest among those. These kids have above-average intelligence, and behave casually and confidently. As a result of the way they behave, they are fun for adults to watch. The adults therefore watch them, and the kids pick up on this. My job, the kids say to themselves, is to give those grown-ups something to watch.

And this starts a vicious cycle of accelerated learning. The children already have, before the age of two, a kind of sense of responsibility. They understand that they have a direct effect on the outcome of things. That’s a heady sense of self to have at such a tender age. Before the age of three, this becomes second-nature. Grown-ups can be sad, grown-ups can be happy, and the child can decide this.

When you learn something that soon, it’s impossible to forget it. Ever.

Now, this doesn’t happen to everybody. There are other kids who have trouble relating to the adults and their peers. Age two comes and goes, then age three, then age four; these children have yet to take command of their environment, to find a way to impact the mood of those around them. As a result, they aren’t expected to do much of anything. Except, maybe, do some chores. They expect no more of themselves, in communicating with others, than others expect of them. They lack the confidence their more mature siblings and peers have, and wear day-to-day rather easily. They lack this confidence, and therefore they lack the ability to command the attention in a group setting. This continues for a great deal of time. They may be double, triple, quadruple the age their more outgoing peers were, upon easily attaining this commanding, communicative skill. And they have yet to grasp it. They go tumbling into adolescence this way.

But while all this is going on, a funny thing happens. These less-mature kids, who are quieter, more contemplative — less fun to watch — sooner or later, are left alone. And then they have to find something to do.

This pattern never seems to change: The highly-educated and highly-esteemed scientific professionals, fail to keep it in mind. Kids, young and old, smart and dumb…they all have to be occupied. If they tend to bore the grown-ups so that the grown-ups don’t give them anything to do, they will find something to do. They will make “projects” for themselves. And that is exactly what these not-so-mature, not-so-sociable kids do. They write, they draw, they paint.

They accumulate skills. Skills their more outgoing peers don’t develop…because there’s no need to. The more sociable kids have other skills, which the reading-drawing-painting kids are never going to have. Not naturally, anyway.

This is Yin and Yang. Yang kids become chatty, and demonstrate amazing aptitude in being that way, by the age of two or three. The socially immature Yin drift around for a few more years, wondering what to do, and then start developing cognitive problem-solving skills between the ages of five to eight. Yang expect to be watched, Yin expect not to be. Both become self-fulfilling prophecies. On a day-to-day basis. For life.

Now, let’s talk about brainwave activity. I’m no more a neurosurgeon than I am a shrink. But there exists a lobe called the Orbito-Frontal Cortex, and what’s cool about this particular lobe is that it remains a mystery to science. You don’t need to do too much homework about it before you know — painstaking details, useful only in a laboratory setting, aside — everything the scientists know. At least, all the stuff they know for sure. And that’s not much.

The Orbito-Frontal Cortex, or OFC, is one of the least understood regions of the brain. Part of the reason for this is that, for all the importance it seems to have, it defies conventional brainscan methodologies. It’s located too close to the sinus cavity to be mapped as effectively as other regions. All that air whooshing around in there, and what-not.

The Orbito-Frontal Cortex, or OFC, is one of the least understood regions of the brain. Part of the reason for this is that, for all the importance it seems to have, it defies conventional brainscan methodologies. It’s located too close to the sinus cavity to be mapped as effectively as other regions. All that air whooshing around in there, and what-not.

And so science has been working hard on figuring out how this piece of meat works. And it’s been able to nail down relatively little.

But science does know a thing or two at this point. And what they’ve been able to learn about the OFC, is — roughly — this: We process reward and punishment through this part of the brain. The way this isolated region takes charge of this chore, it can be said, is readily apparent to everyone who has one. You put your hand on a hot stove, and years later, you see another hot stove. You aren’t cataloguing facts, things you can learn from the facts, cataloguing things you don’t know, engaging in process of elimination, or anything of the kind…you just know you don’t want to touch it. Carrots and sticks. They cause a “short-circuiting” to occur upstairs. You don’t know what you do & don’t know…nor do you care. You haven’t a clue. On what you want to do and don’t want to do, you’re crystal-clear already, so something must have been engaged out-of-sequence. The OFC, it’s fairly well established, is the corridor through which that short-circuiting occurs.

The OFC also has to do with engaging us with each other socially. When we ingratiate ourselves with groups, cliques, subcultures, and the like, we engage the OFC. There are things that are “done” and there are other things that are “not done.” A great example of this is wearing white after Labor Day; rare is the fashion maven that can actually explain what’s wrong with doing this, but they all agree it’s something that simply isn’t done.

Reward and punishment. It goes through the OFC.

Well it turns out, when we aren’t paying attention to others and others are not paying attention to us, and we’re locked in our bedrooms designing our dream houses or fingerpainting or whatever, the OFC doesn’t have a lot of use for us. And so these Yin children who become accustomed to doodling throughout their childhood and teenage years, over time become sluggish engaging OFC-related intellectual exercises. Perhaps their OFCs shrivel up like raisins. Or perhaps the synapses that connect the OFC, become rusty and corroded. Whatever the physical cause, it remains a truism that the brain reprograms itself as it is engaged in everyday tasks. These Yin kids, once they’re placed in a more socially-interactive setting and thus given a cause to re-engage this atrophied OFC, they tend to adapt sluggishly.

Maybe the chubby ones who are used to stuffing their faces with Cheetos and chips while watching Beavis and Butthead, in the middle of asking a prom date to dance, will burp right in her face. More often, the examples will be subtle. Kids who are relatively inexperienced at relating to other kids, will be forced to learn how…and if they’re intelligent and flexible, they will. If they spend enough energy, they may even become almost as socially-outgoing as the more sociable kids, who did exactly the same thing at a far younger age.

But they won’t do it the same way. They communicate with their peers and start socializing, even if they enjoy the company — they still see the other party as kind of a puzzle. They see external entities in ways the Yang kids do not see them. They labor onward, Yin in Yang’s clothing, doing these Yang-things unnaturally but, with sufficient attention and energy, with some proficiency. Upstairs, they’re going through all these extra steps. I know this, I don’t know that…from that, I’m to conclude that…and therefore, I shall do this. Chances of her dancing with me if I burp in her face, 20%…chances if I don’t burp in her face, 45%…therefore, I shall not burp in her face. Like someone playing chess, or Master Mind.

The Yang-kids do exactly the same things. But they do it by engaging the OFC. It’s all one easy, fluid motion.

Yang kids are no different. If they’re very intelligent and mature, and keep that maturity into adulthood, and are greeted with disappointment and use their aptitudes to develop Yin-like skills to overcome those disappointments — they won’t do it the way natural-born Yin kids do it. It’s a case of “when you’ve got a shiny golden hammer, everything looks like a nail.” They may learn how to work with spreadsheets and engineering drawings, but every miniscule task that comes up, they’ll fire up the OFC in ways the Yin kids will not when doing the same thing.

In the years since I’ve become aware of this, I’ve found it’s difficult to categorize people this way when they are intelligent, flexible, talented and bright. You have to figure out where they’re coming from — if a brainscan appliance isn’t available — through their weaknesses. If they’re too smart, they become talented at covering this up. I’ll talk more on this further down.

But none of this means the Yin/Yang orientation is not there. It is brain-lobe routing. It is a distinction between ways of thinking, which become more and more prevalent each day we’re called-upon to solve problems. Everybody has it in one flavor or another.

This reads a lot, I’m sure, like introverts and extraverts. That isn’t really what’s going on, when you look into the details of the definitions. Introverts and extraverts run “on batteries” in certain situations. They may adapt to something outside their turf for a little while, but they consume energy in doing this. Introverts speak in public — their energy is depleted and they will restore it in solitude. They’ll look forward to Friday evening, and once the weekend is here they will grab some beer and go fishing. Alone. Extraverts may hole themselves up in their offices and fiddle around with spreadsheets and databases…when they’re forced to. In so doing they’ll deplete energy. They’ll rejuvenate by doing exactly the things that drain the energy of the introverts. They’ll hold court. With big smiles on their faces…smiles that were missing when they were fiddling around with the Godforsaken spreadsheets they didn’t really want to fiddle with.

Must a Yang be extraverted? No. An extravert loses energy in solitude and rejuvenates it in a large group; a Yang channels intellectual challenges through the OFC, that need not be channeled there. To be an introverted Yang, all you have to do is operate on a reward-and-punishment basis, and look forward to operating in solitude.

Perfectly possible. It would probably be difficult to implement such a combination and to be happy. But it’s definitely possible.

Must a Yin be introverted? Again, no. A Yin solves intellectual problems systematically. He is most comfortable making a catalogue of things he knows and things he doesn’t know, and proceeding from there to figuring out what’s going on. Being introverted means you deplete your energy in groups of people, whether you’re afraid of them or not — and you recoup that energy in solitude.

Now, groups of people tend to be distracting to the process of gathering evidence and arriving at inferences. But if you’re capable of focusing your attention, and juggling many tasks at once, it can be done. So an extraverted Yin would be someone who enjoys people and also enjoys solving problems.

Also this detail makes it tough to arrive at a razor-precise definition of what separates Yin from Yang. There are two tests, one to be implemented in childhood and one to be implemented after the subject has arrived at maturity.

The childhood test is this:

The Yang Child is stuck in an endless loop of approaching his parents, or parent-figures, and saying: “Look at me.” He feels uncomfortable if he isn’t being watched. Kids like this love to be photographed, but if you watch them later on you’ll notice they don’t have much interest in the photograph albums. They want to be watched in the here-and-now. They see the world as a stage, and they want to be actors.

The Yin Child, on the other hand, is stuck in a different endless loop. He gains attention and approval from his parents by saying — not “Look at me” — but “Look what I did.” He doesn’t care to be watched and if he is watched, he cares little about what people will see. He busies himself with manufacturing things, or designing things, and showing his wares after he is done with them.

This hasn’t got much to do with shyness, except to say shyness is a causative factor in becoming Yin. It’s highly difficult for a shy kid to go the other way. This arouses a popularly-held belief that when children behave in introverted ways, they must be shy. That’s bad logic at work; it’s like saying all fish must live in the water, therefore anything that lives in the water is a fish. One’s a superset of another, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the sets are identical.

The test to be applied after maturity is even more complicated. It works this way:

You can see the difference between Yin and Yang, in adults, most clearly when there is a new tool to be used. In our times, the best example of that is when Microsoft releases a new version of an operating system, or of a component in the Office Suite.

Some of us look forward to this. Others dread it.

Now if a new bit of technology comes out, and you’re tasked with educating the uninitiated about how to use it, after awhile you’ll be able to easily make this distinction yourself. You can see it in the way some of your students behave: The Edit menu in the old version, had nine sub-options, and now it has eleven…they have a great enthusiasm in learning about the other two. The other students are going to behave in a manner completely different: They’ll be frustrated. God damn it, I know what I want to do…I used to have a way of doing it and then they released this piece-o-crap program and now I have to do it all over again. In other words, they don’t see the benefit. And if you work with them for awhile, this becomes understandable — they don’t get a benefit out of it.

They exist to socialize, and every now and then there are tasks that have to be done. Tools are simply ways to achieve those tasks. A new tool comes out…so what? If the old tool accomplished the task just as efficiently, the upgrade is a futility.

I’ve been put in this position more than my share of times. And I know this for a fact: Anybody else, who has been put in the same position, understands what I’m saying. Some students are tool-oriented, and others aren’t.

What never seems to change, is this: The tool-oriented people are moderately, or sub-par, sociable. The non-tool-oriented people are social butterflies.

Really, adults can be tested with any challenge that is new. That is the operative concept here. Adults, once met with a challenge that they’ve already dealt with before, have a tendency to go with whatever plan they used the last go ’round whether it was successful or not. Force them to come up with a new one, and you’ll have a great test of Yin vs. Yang.

Probably the most generic of these, is to ask articulate, but unintelligible, questions. “Maybe I’m asking the wrong person, but can you tell me…” and, following that, hit ’em with something containing at least one completely unfamiliar verb, and two completely unfamiliar nouns. Whatever the adult’s leanings, he will then have to busy himself with figuring out if he can help you, and then finding a way to do it.

The way the Yin see the world, everything worth doing involves a state of objects as they are, and a state of objects as desired — the work to be done lies in the difference between those two states. You are trying to do something; the subject of your test doesn’t yet know what it is. What he’s going to try to do, is find out what your mission is, and from that figure out if he’s able to help you. Perhaps you want to break the law, or perhaps you want to help his competition succeed. Step One is going to be to eliminate those as possibilities. Step Two is going to be to measure the magnitude of work. All tasks, to the Yin, occur within a perimeter. Replacing the exhaust manifold on a Chevy Malibu has to be done one time — that’s measurable. Printing up five thousand fliers has to be done 5,000 times — that’s measurable. This has a bearing on the method to be pursued getting these things done…for example, if you only want ten fliers instead of 5,000, you’ll be wanting to do that on your home printer most likely.

But the Yin, being entirely unfamiliar with what you want to do, will make these questions a priority.

And after the conversation is over, if your work is interesting the Yin will be hitting the Internet to find out more about it. You used acronyms and terms he didn’t know, and he doesn’t want to be blindsided again if someone else has a related question…that stuff’s interesting, after all.

The Yang react in a similar way, but they show different behaviors before the exercise is over. For starters — when you first asked the Yang your question, he, likewise, didn’t understand what you were talking about. The Yang find situations like these to be tinged with a residual hue of threat: If you talk about things they don’t understand, you may represent an entirely different kind of people.

You are going to labor under a time limit to make yourself understandable to the Yang. If you do not meet it, the conversation will be over. They’ll politely refer you to someone who might possibly know more about what you’re trying to do. There won’t be a lot of responsibility taken to make sure this is the case; about half the time, you’ll find it’s a bunny trail. What really happened was, you blindsided the Yang with something that was unfamiliar. He allocated a certain amount of time to venture in here with you, and you exhausted that quota. Think how you’d behave around a stranger who at first seemed to have all his mental faculties about him, and then as he proceeded to spew a lot of gibberish at you, demonstrated himself to be certifiably insane. That’s what happens with the Yang. You might be sane, but discussing something outside of their comfort zone — to them, that’s the same as being insane.

So you’ve got about forty-five seconds. If you explain what you’re trying to find, or what you’re trying to do, in a way that makes sense to him inside that limit, he’ll go down a different path. The first thing he’ll want to know is: What effect is this going to have? If it’s something that will benefit you personally, like replacing the exhaust manifold, he’ll see this as the beginning of a friendship and his questions will start to take on that tone: Tell me about yourself. Where are you from? What do you do? He’s trying to get on a little more solid footing with you, as a future friend. They’re sociable creatures. You have stories, he has stories, if you exchange stories you’re both four times as story-rich as you were before. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and all that.

With regard to printing up the fliers, he’ll ask a question the Yin forgot entirely to ask: What is going on them? If it’s a political slogan, the Yang’s enthusiasm for helping you will wax or wane depending on his sympathies with the message going on the fliers. If it’s political-neutral — for example, come to our church dinner, the cover charge goes toward feeding the hungry — this will have an immediate effect on his enthusiasm as well. And as you talk with him about it, you’ll see he doesn’t regard this as a mission for your church. He sees it as a way to feed a portion of the world’s hungry people.

Remember the perimeter that the Yin see surrounding all tasks? That’s a defining difference there. The Yang don’t see it. They see the world…as one object. The world’s got so many cars that need new exhaust manifolds, and it’s got so many kids that are so hungry. After the project is completed, there will be slightly fewer cars that need new manifolds, or slightly fewer hungry kids. A project did not get completed — a task is what got completed. The completion of an actual project is something the Yang very rarely knows, because as far as they’re concerned, it is the complete eradication of something. Dirt. Crime. Poverty. The things that are worth our time, involve noble, incremental baby-steps toward those kinds of great, wonderful goals.

From this, we see adulthood is merely an extension of what we have all done in childhood. Shut in to our offices, laboring in solitude over a meaningless spreadsheet…or possibly, a future cure for cancer…the way the Yin do things, makes a great deal of sense. You know some things, you don’t know other things. From this, some things may be, other things must not be. And if it makes someone somewhere feel bad, that matters not one bit.

But in groups, the way the Yang do things, is the more sensible way to go. They take these puzzles, which to a nice Yinny born-and-bred puzzle-solver might actually be quite simple…and they punt. They scrape it all into a bottomless manhole somewhere in the OFC. And from the OFC, it goes into some massive antennae — which the Yin, decidedly, lack — and they synchronize with a group to find the correct answer. In effect, they externalize the exercise. They put it to a vote. Does this make sense? Logically, no. But socially, yes. And it involves some measure of skill in it’s own way.

You can kind of start to see why one of these “sides” is friendly to individualism and the other “side” is friendly to socialism and collectivism.

That’s why there is so much friction any time Yin and Yang are forced to function in close proximity to each other. The things that need to be done, they don’t see them the same way. “Mission Accomplished” means a completely different thing to one side than it does to the other.

Now, these tests are imperfect. It can take some effort to apply them, get results back, and figure out what they mean. Persons of average intelligence, or slightly higher — this distinction jumps out at you and grabs you by the neck. It’s impossible to ignore. When you deal with people slightly more intelligent than that, like significantly over the average, bordering on genius levels, this becomes a much more subtle distinction.

The subtlety is a problem with highly intelligent, highly functional people. Experience has a bearing on this as well. Persons of lower intelligence, ten or fifteen I.Q. points over the average, can hang around and gradually accumulate methods and tactics for dealing with everyday problems. They start to learn when they’re creeping people out by not being talkative enough, or annoying others by being too talkative. And they solve everyday problems with familiar tools. Highly experienced people like this, it can be very difficult to figure out if they’re Yin or Yang. And your incentive for doing so will soften up as well — you’re not running into problems with the way they go about doing things, so why bother to figure it out?

But as to whether these people really are Yin or Yang within their cranial cavities — this changes nothing. They still are devoted to one side. A new challenge comes up — they’ll noodle it out according to what can be learned, verified, repudiated…or they’ll select an option they anticipate will be pleasing to their peer group. All of one & none of the other, or vice-versa.

There’s no middle ground here. None whatsoever.

Earlier this year, I had tracked down a management training exercise I had personally attended ten years previous. I found the management training exercise to be a problematic illustration of human nature at best, and an outright lie at worst.

There was a point to the exercise, and for the purpose of making this point, it was positioned in the Arctic tundra, miles from civilization. Choices had to be made about tools, supplies, things to be done…and to make these choices, the group was declared supreme, and the individual decidedly inferior. The exercise demonstrated that the group amounted to something greater than the sum of it’s parts. By sticking together, asserting themselves at the right time, deferring at the right time, the individuals contributed to a group that made the right decision all the time. Or more often than any one of its members, effectively saving the lives of all who participated.

I had a minor beef with this at thirty years of age. Past forty, I am weary, jaundiced, and…what can I say. I know better. I’ve watched individuals solve problems and I’ve watched groups solve problems.

Groups don’t really solve problems. If there’s a problem to be solved — “Should we put the sleeping bags on dry ground first, or gather firewood?” “Is it realistic to build a flat-six air-cooled engine?” “What is the square root of 841?” — groups don’t solve this. They delegate it to an individual. If the group solves the problem, they do it by swivelling all heads toward the guy who knows best, and then that guy comes up with an answer. As an individual.

The closest a group gets to doing something an individual can’t, is allocating money for things. Sub-groups don’t want to contribute to a cause, without representation…so you represent all of them. A group is born. With the money thus allocated, an individual comes from somewhere and does the real work. Then the group takes credit for it.

But groups do think. That is the problem. This is the most likely evolutionary purpose of the OFC. It provides us, as individuals, with the ability to quickly process punishment and reward…and therefore more cohesively integrate ourselves into a group. With our luminous and vibrant OFCs, we can understand some things are “good” and some things are “bad,” before we’ve wasted time trying to figure out (as individuals) what makes these things good or bad. I before E except after C…salad fork goes outside the dinner fork. Nevermind what actually is going to happen if you bring pork to a Jewish wedding, just don’t do it.

That’s what allows us to make up groups, and to function within them.

But the Schefferville exercise is…well, it’s crap. Groups don’t solve problems better than individuals. They don’t solve problems at all. What they do is generate instant credibility, without putting anyone in the situation of being held accountable. And they make it expedient to create compromises. Therefore, they can allocate money. But they don’t think. Thinking in the group is done with the OFCs, and that isn’t real thinking. It’s simple anticipation of reward and fear of punishment, nothing more.

With that lengthy exploration, we now come to James’ article…which I find fascinating. Here’s how it works.

The test is administered, and probably designed, by one Boaz Keysar. He teaches at the University of Chicago. His biography page says the following:

Professor Keysar’s research is about how people communicate, negotiate and make decisions. Many of his discoveries reveal systematic reasons for miscommunication and misunderstandings. For example, his research shows that people overestimate their ability to communicate accurately, and counter to what people tend to think, we miscommunicate even more with those who are more familiar to us.

So what about this test he designed. Well, let’s take a look.

Rugged American individualism could hinder our ability to understand other peoples’ point of view, a new study suggests.

And in contrast, the researchers found that Chinese are more skilled at understanding other people’s perspectives, possibly because they live in a more “collectivist” society.

:

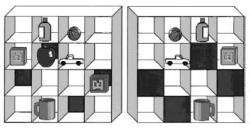

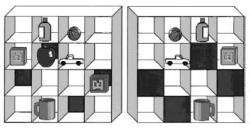

Keysar and his colleagues arranged two blocks on a table so participants could see both. However, a piece of cardboard obstructed the view of one block so a “director,” sitting across from the participant, could only see one block.

When the director asked 20 American participants (none of Asian descent) to move a block, most were confused as to which block to move and did not take into account the director’s perspective. Even though they could have deduced that, from the director’s seat, only one block was on the table.

Most of the 20 Chinese participants, however, were not confused by the hidden block and knew exactly which block the director was referring to. While following directions was relatively simple for the Chinese, it took Americans twice as long to move a block.

The test is explained in much greater detail in this article from last week in the New Scientist:

In a new psychological experiment, Chinese students outperformed their US counterparts when ask[ed] to infer another person’s perspective. The researchers say the findings help explain how misunderstandings can occur in cross-cultural communication.

In the experiment, psychologists Boaz Keysar and Shali Wu at the University of Chicago, Illinois, US, recruited 40 students. Half of the volunteers were non-Asians who had grown up in the US, and the other half were native Mandarin speakers who had very recently emigrated from various parts of China.

In the experiment, psychologists Boaz Keysar and Shali Wu at the University of Chicago, Illinois, US, recruited 40 students. Half of the volunteers were non-Asians who had grown up in the US, and the other half were native Mandarin speakers who had very recently emigrated from various parts of China.

The volunteers played a game in which they had to follow the instructions of a person sitting across the table from them, an individual known as the ‘director’.

Researchers placed a grid structure between the two people consisting of small compartments, some of which contained objects such as wood blocks, toy bunnies and sunglasses (see image, right). Some of the individual compartments were covered on one side with cardboard so that they were blocked from the view of the director – only the study subjects could see the objects inside.

The volunteers had to follow the instructions of the director and move named objects from one compartment to another. But – as a sneaky trick – the researchers sometimes placed two objects of the same kind in the grid. In this case, the subjects would have to consider the director’s view to know which object she was referring to.

For example, the grid sometimes contained two wooden blocks, one of which sat in a compartment hidden to the director. The director would then ask the subject to “move the wooden block to a higher square in the grid”.

Chinese students would immediately understand which wooden block to move – the one visible to both them and the director. Their US counterparts, however, did not always catch on.

“They would ask ‘Which block?’ or ‘You mean the one on the right?”, explains Keysar. “For me it was really stunning because all of the information is there. You don’t need to ask,” he adds.

Now, for the purposes of figuring out what’s wrong with the test, it isn’t important to figure out if Dr. Keysar is oblivious to what he’s so obviously missed, or if he’s hoping his intended audience remains so oblivious. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that his test is flawed.

You have these two roles to play, the “participant” and the “director.” The “director” issues commands, the “participant” carries them out — but the “participant” understands all of the objects that are involved in what’s being done, whereas the “director” has knowledge only of some of them.

The shots, therefore, are called by the ignorant party.

This means the test is a test of ability of the participant to reject reality. To subordinate that which is known to be real, on a verifiable, individual level — to what has been dictated by an external entity, known to lack all of the information needed to make the correct decision.

Note how this test is titled and how it is described: “Self-centered cultures narrow your viewpoint.” “Study: Americans Don’t Understand Others.” You may understand reality — like the Yin — or you may understand others, like the Yang. Arbitrarily, from the way the headlines are written-up, the understanding of others is given priority. Those who are accustomed to using the OFC to do their “thinking,” want all others to do likewise. To abjure reality in favor of complying with the lessons of arbitrary, ignorant authority…with the lessons of reward and punishment.

But the OFC doesn’t understand math. It doesn’t understand fact, opinion, thing-to-do. It doesn’t understand process-of-elimination or rhetorical questions or cause-and-effect. The OFC only understands one thing: Do this, instead of that. X good, Y bad.

Dr. Keysar and associates’ critical error, was to either misunderstand this or to subordinate it. You can solve problems in such a manner as you, personally, can verify that you’ve correctly solved the problem…or you can follow instructions. Those are two distinctly different exercises. The researchers have found Americans have shifted their priorities away from following instructions, identifying with persons left ignorant by design…and toward arriving at the correct answer to the problem-at-hand.

There is a crucial distinction to be made here. The “participant” was being tested on his ability to denounce reality as he understood it, in favor of the instructions of a “director.” If this was a test about productive humility, the possibility would have been left open that perhaps “director” knew some things the “participant” did not. Perhaps there was a body of knowledge applicable to the test at hand, which could have been understood in total by a careful collaboration between “director” and “participant” so the two parties could pool their respective knowledge bases — a collaboration demanding more time than was immediately available. Or perhaps, although ignorant about some of the details, “director” may have had a prevailing command of more important items, denied to “participant” — things that would have lended greater weight to the integrity of chain-of-command. Or, yet another possibility could have been left open: “Director” knew all, but only pretended to be ignorant of some. Maybe the possibility existed that “participant” only thought he understood everything, but was kept in the dark about “surprises.”

None of these things seem to be applicable to the test as I understand it. From all the descriptions I’ve read — “participant” understood everything; “director” understood only some and misunderstood a great deal beyond that; “participant” was fully conscious of what he knew, how complete his understanding was, and what bits of detail were denied to “director.”

If I’m getting that right, I must suck at this test more than most. I don’t understand why you’d want a good score! It looks like a test in one’s ability to hallucinate. To pretend others are right, when you know they’re wrong.

Why was this test designed the way it was? And why was it publicized the way it was? The Chinese “understand peoples’ point of view” better than Americans. But the way they demonstrate this understanding in the experiment, has nothing whatsoever to do with “understanding.” What they have done is execute a move in a way they were expected to execute it…by a “director” who was kept deliberately ignorant about what was going on, as he issued his edicts.

You know what? A wood chisel, positioned underneath a rubber mallet, accomplishes that just dandy. With no “understanding” of anything whatsoever.

You know what? A wood chisel, positioned underneath a rubber mallet, accomplishes that just dandy. With no “understanding” of anything whatsoever.

No, I’m not trying to put down the Chinese. I’m just making a point: Doing what you’re told, no more no less, has nothing — nada, butkus, zilch — to do with “understanding” much of anything at all. That isn’t even science, it’s just common sense.

And I think the researchers can see that. So why proceed with this “test”?

This has been intriguing me for a long time. Tests like these, I think, are built to showcase the good side of collectivist societies, and the bad side of individualist societies. And this is the latest in a series. You don’t want to be holding your breath waiting for a scientific test to come out, that shows off how well individualist societies perform — although if such an endeavor were to be undertaken, there are all kinds of things that could be studied. But we don’t see research like that. We see research about people being better off when they live life for the sake of others. Recall the Schefferville exercise discussed above. That’s what I’m talking about. That’s the way this “research” always goes.

Now, why is that? It isn’t “science.” Science doesn’t have a lot to do with this kind of mythology. Science hasn’t got much to do with socialism…not in theory, and not in practice. What’s with all these propeller-beanie eggheads trying to foist this socialism off on us? What’s in it for them?

I vote for human nature. For quite a few years now, I’ve noticed how many among the Yang seem to be highly motivated toward forcing the Yin to see things as they do…to live life the way the Yang live it. I think it’s simply in their nature. Yin can live-and-let-live; Yang seem to have a big problem with this. The Yang see the world as a single object, so to them, borders are meaningless. You don’t want people in the world to suffer, borders are just going to get in the way — they chop up the project at hand, into useless little bits. Keep the borders, and you’ve got to worry about ending suffering in Uganda, then in Chad, then in Somalia, and then in the United Kingdom…what’s the point? Besides, they make it easier to miss something.

So out they go, and since we’re doing away with international borders we have to get rid of other borders as well. The concept is the same. You want your house to appreciate in value, I want my house to appreciate in value…if we draw a boundary between our yards, we introduce a potential that one of us can realize the goal, while the other neighbor fails. It’s a fifty-fifty shot. Why not just do away with that, and then we can work together as a team?

Another thing that I think might motivate tests like this one, is plain old-fashioned jealousy. The goofy Yinny-headed “Americans” don’t do well on the test because they’re worried about giving the answer that reconciles against reality, rather than the answer that reconciles against the arbitrary notions of this ignorant “director.” You know, say what you want about that…but you know it’s correct. You don’t like to see someone else doing it, when you’ve pledged fidelity toward doing things the other way. Deep down, I think we all see the logic in this — make the decision that is correct, according to the world as it really is. Who cares what others say? If reality blesses you, all other blessings will follow. If you aren’t sure it’s the right answer, find out more. If you can’t find out more, then proceed according to what you know and not according to what somebody else knows. I think everyone understands, this just makes sense.

To pump out all this “research” nudging people toward the idea that you should do things the opposite way — it’s just jealousy. Since we all know that’s the right way to go, we don’t want someone else doing it after we’ve decided not to.

It’s like watching a woman get mugged, and making the choice not to get involved. You might feel kind of alright about it, if you’re enough of a creep and you manage to keep yourself detached. You might even look good to someone else who also chooses not to get involved…or who can’t get involved. But a complete stranger decides to jump in and helps her after you’ve taken a pass, you’re going to feel terrible about it, if there’s so much as a shred of decency left in you, and there’s no way you can come out of it looking good.

And so people who opt out of individualism, end up wanting to cleanse the entire planet of every tincture of it. It’ll happen that way every time. Individualists can live with non-individualists; but non-individualists cannot abide individualists. A collectivist society must span an island…then the adjoining continent…and eventually, the entire globe. This is how collectivism must work; it is monopolism. It’s gotta be that way. It was true eons before my parents met, and it will remain true long after my bones are dust.

In both George W Bush’s presidential victories, he managed to secure a vast majority of the evangelical Christian vote.

In both George W Bush’s presidential victories, he managed to secure a vast majority of the evangelical Christian vote. I have been

I have been  Let me introduce a theory to help explain this. Let’s call it the “Big Gray Building” theory; we will take all of your formative years, stretching deep into adulthood in which, as your maturing personality develops skills to meet rising challenges in the business world, you do this crossing-over. This writing-with-the-other-hand.

Let me introduce a theory to help explain this. Let’s call it the “Big Gray Building” theory; we will take all of your formative years, stretching deep into adulthood in which, as your maturing personality develops skills to meet rising challenges in the business world, you do this crossing-over. This writing-with-the-other-hand. If they lack the maturity to build a network involving peers or parents, they’ll have to be forced into it. But if that’s the situation, they won’t naturally take to it. They’ll do it when forced to do it. And meanwhile, if they have any intelligence at all, they will become adept at solving problems. This is simply path of least resistance. Being children, they will have to challenge themselves, and if the socializing presents too much of a challenge they’ll find a challenge that doesn’t involve socializing. They will crawl — more like shoot — due North along the street I’ve called “Rain Man Lane” — developing cognitive ability while neglecting, to some degree, social skills. And they can’t turn corners, so they’ll be stuck up there once they reach the end. They’ll become “nerds,” seeking out more and more challenges that don’t involve interacting with people. Let’s say there is a “library” up there. They will pop over to this virtual library at around age five, and stick around there. They’ll remain there until, roughly, the age they can start driving.

If they lack the maturity to build a network involving peers or parents, they’ll have to be forced into it. But if that’s the situation, they won’t naturally take to it. They’ll do it when forced to do it. And meanwhile, if they have any intelligence at all, they will become adept at solving problems. This is simply path of least resistance. Being children, they will have to challenge themselves, and if the socializing presents too much of a challenge they’ll find a challenge that doesn’t involve socializing. They will crawl — more like shoot — due North along the street I’ve called “Rain Man Lane” — developing cognitive ability while neglecting, to some degree, social skills. And they can’t turn corners, so they’ll be stuck up there once they reach the end. They’ll become “nerds,” seeking out more and more challenges that don’t involve interacting with people. Let’s say there is a “library” up there. They will pop over to this virtual library at around age five, and stick around there. They’ll remain there until, roughly, the age they can start driving. Now, some children will have the maturity to build the above-mentioned parent-peer network. And at a very early age, on the light side of two years old, they’ll shoot off Eastward along “Valley Girl Street,” toward a “social club.” These sociable kids can’t turn a corner any better than their nerdy counterparts, even if they’re very mature and intelligent. This favored pastime of socializing people, just burns too brightly and is too tempting for them. Even with homework and exams and so forth, there is little point to nurturing problem-solving skill. The need just isn’t there.

Now, some children will have the maturity to build the above-mentioned parent-peer network. And at a very early age, on the light side of two years old, they’ll shoot off Eastward along “Valley Girl Street,” toward a “social club.” These sociable kids can’t turn a corner any better than their nerdy counterparts, even if they’re very mature and intelligent. This favored pastime of socializing people, just burns too brightly and is too tempting for them. Even with homework and exams and so forth, there is little point to nurturing problem-solving skill. The need just isn’t there. So now our block is complete: You’re born at a corner, there is a library at one corner, a social club at another, and then there’s a business convention going on at the far corner where you won’t arrive, until you’ve become a mature adult. Not a twenty-something, but someone with the maturity to achieve functional command of the spectrum. Since kids lack the ability to round corners, and childhood itself runs light on challenges that make real demands to do such corner-rounding…each set of child is stuck in his respective corner. Adulthood, probably, will bring a fresh wave of challenges. These challenges will, at long last, demand this corner-rounding — accepting no substitute for it. The child who crawled East will have to crawl North, and vice-versa…the business convention is at that inconveniently-located corner after all.

So now our block is complete: You’re born at a corner, there is a library at one corner, a social club at another, and then there’s a business convention going on at the far corner where you won’t arrive, until you’ve become a mature adult. Not a twenty-something, but someone with the maturity to achieve functional command of the spectrum. Since kids lack the ability to round corners, and childhood itself runs light on challenges that make real demands to do such corner-rounding…each set of child is stuck in his respective corner. Adulthood, probably, will bring a fresh wave of challenges. These challenges will, at long last, demand this corner-rounding — accepting no substitute for it. The child who crawled East will have to crawl North, and vice-versa…the business convention is at that inconveniently-located corner after all. And as far as the path they have taken, there is no middle ground. At least, that’s the theory. Remember, the big gray building is monolithic. For a socially-exuberant child to develop real problem solving skills, is improbable because it’s unnatural. Children develop skills wherever need intersects with opportunity. They have to have both, or the development is highly unlikely to take place…and the socially-energetic kids don’t have need. As for the socially-interactive skills developing in the nerds, that’s a matter of opportunity. It’s absent, and so they go for the next best thing. They develop the ability to think out unorthodox challenges through a cognitive process, an ability their more friendly and outgoing counterparts invariably lack.

And as far as the path they have taken, there is no middle ground. At least, that’s the theory. Remember, the big gray building is monolithic. For a socially-exuberant child to develop real problem solving skills, is improbable because it’s unnatural. Children develop skills wherever need intersects with opportunity. They have to have both, or the development is highly unlikely to take place…and the socially-energetic kids don’t have need. As for the socially-interactive skills developing in the nerds, that’s a matter of opportunity. It’s absent, and so they go for the next best thing. They develop the ability to think out unorthodox challenges through a cognitive process, an ability their more friendly and outgoing counterparts invariably lack. I find this to be ironic. This movie should be considered a warning to all bloggers, conservative and liberal — and overzealous activist judges who run around striking down any law they personally dislike, under some rancid and overly-delicate “interpretation” of the “Constitution,” jotting down any ol’ text to justify the decision they’ve already made before they cooked up a single word of the opinion. The movie applies to this pretty well. It, like all great ones, is about two stories: The cosmetic one that skims along the surface, and the deeper one that labors on in parallel far beneath. The visible and shallow story has to do with five grad students living in a cottage, growing vegetables, going to school, wallowing in their liberal-ness and feeling really smug about it. They pontificate a whole lot and they actually ponder very little. Their only point of disagreement, at first, is about whether it should be allowable to turn on the boob-tube when a certain bloated conservative media icon, obviously modeled after Rush Limbaugh, spews his hated right-wing venom on television.

I find this to be ironic. This movie should be considered a warning to all bloggers, conservative and liberal — and overzealous activist judges who run around striking down any law they personally dislike, under some rancid and overly-delicate “interpretation” of the “Constitution,” jotting down any ol’ text to justify the decision they’ve already made before they cooked up a single word of the opinion. The movie applies to this pretty well. It, like all great ones, is about two stories: The cosmetic one that skims along the surface, and the deeper one that labors on in parallel far beneath. The visible and shallow story has to do with five grad students living in a cottage, growing vegetables, going to school, wallowing in their liberal-ness and feeling really smug about it. They pontificate a whole lot and they actually ponder very little. Their only point of disagreement, at first, is about whether it should be allowable to turn on the boob-tube when a certain bloated conservative media icon, obviously modeled after Rush Limbaugh, spews his hated right-wing venom on television. And along comes Michael Moore. Moore, for reasons I don’t understand and no one seems to be able to tell me, gets a pass. Over and over again, he’s caught red-handed with his lyning-by-omission and his half-truths and his bad-faith dealings with the subjects of his “interviews.”

And along comes Michael Moore. Moore, for reasons I don’t understand and no one seems to be able to tell me, gets a pass. Over and over again, he’s caught red-handed with his lyning-by-omission and his half-truths and his bad-faith dealings with the subjects of his “interviews.” The Orbito-Frontal Cortex, or OFC, is one of the least understood regions of the brain. Part of the reason for this is that, for all the importance it seems to have, it defies conventional brainscan methodologies. It’s located too close to the sinus cavity to be mapped as effectively as other regions. All that air whooshing around in there, and what-not.

The Orbito-Frontal Cortex, or OFC, is one of the least understood regions of the brain. Part of the reason for this is that, for all the importance it seems to have, it defies conventional brainscan methodologies. It’s located too close to the sinus cavity to be mapped as effectively as other regions. All that air whooshing around in there, and what-not. In the experiment, psychologists Boaz Keysar and Shali Wu at the University of Chicago, Illinois, US, recruited 40 students. Half of the volunteers were non-Asians who had grown up in the US, and the other half were native Mandarin speakers who had very recently emigrated from various parts of China.

In the experiment, psychologists Boaz Keysar and Shali Wu at the University of Chicago, Illinois, US, recruited 40 students. Half of the volunteers were non-Asians who had grown up in the US, and the other half were native Mandarin speakers who had very recently emigrated from various parts of China. You know what? A wood chisel, positioned underneath a rubber mallet, accomplishes that just dandy. With no “understanding” of anything whatsoever.

You know what? A wood chisel, positioned underneath a rubber mallet, accomplishes that just dandy. With no “understanding” of anything whatsoever. As an ordinary, non-politician, non-felon, non-female American male guy, there are two prospects that really get me interested in a great big hurry: How to get elected officials to do what ordinary men want them to do, and how to get women to do what ordinary men want them to do.

As an ordinary, non-politician, non-felon, non-female American male guy, there are two prospects that really get me interested in a great big hurry: How to get elected officials to do what ordinary men want them to do, and how to get women to do what ordinary men want them to do.

What hardcore leftists like Olberdouche seek to do here, is to create a lot of noise in hopes of promoting an illusion of widespread loathing against President Bush’s policies. This is something they don’t want to discuss directly, because what they seek to defeat is the President’s recognition that some people are just-plain-bad. In their world, everyone is sympathetic, except for Republicans, conservatives, and other people who might obstruct their political agendas. Yeah, it’s really that bad. You saw off some guy’s head while he’s still alive, I call you evil, there’s something terribly wrong with me. You vote Republican and I call you evil…that’s quite alright.

What hardcore leftists like Olberdouche seek to do here, is to create a lot of noise in hopes of promoting an illusion of widespread loathing against President Bush’s policies. This is something they don’t want to discuss directly, because what they seek to defeat is the President’s recognition that some people are just-plain-bad. In their world, everyone is sympathetic, except for Republicans, conservatives, and other people who might obstruct their political agendas. Yeah, it’s really that bad. You saw off some guy’s head while he’s still alive, I call you evil, there’s something terribly wrong with me. You vote Republican and I call you evil…that’s quite alright.