Alarming News: I like Morgan Freeberg. A lot.

American Digest: And I like this from "The Blog That Nobody Reads", because it is -- mostly -- about me. What can I say? I'm on an ego trip today. It won't last.

Anti-Idiotarian Rottweiler: We were following a trackback and thinking "hmmm... this is a bloody excellent post!", and then we realized that it was just part III of, well, three...Damn. I wish I'd written those.

Anti-Idiotarian Rottweiler: ...I just remembered that I found a new blog a short while ago, House of Eratosthenes, that I really like. I like his common sense approach and his curiosity when it comes to why people believe what they believe rather than just what they believe.

Brutally Honest: Morgan Freeberg is brilliant.

Dr. Melissa Clouthier: Morgan Freeberg at House of Eratosthenes (pftthats a mouthful) honors big boned women in skimpy clothing. The picture there is priceless--keep scrolling down.

Exile in Portales: Via Gerard: Morgan Freeberg, a guy with a lot to say. And he speaks The Truth...and it's fascinating stuff. Worth a read, or three. Or six.

Just Muttering: Two nice pieces at House of Eratosthenes, one about a perhaps unintended effect of the Enron mess, and one on the Gore-y environ-movie.

Mein Blogovault: Make "the Blog that No One Reads" one of your daily reads.

The Virginian: I know this post will offend some people, but the author makes some good points.

Poetic Justice: Cletus! Ah gots a laiv one fer yew...

186k Per Second

186k Per Second 4-Block World

4-Block World 84 Rules

84 Rules 9/11 Families

9/11 Families A Big Victory

A Big Victory Ace of Spades HQ

Ace of Spades HQ Adam's Blog

Adam's Blog After Grog Blog

After Grog Blog Alarming News

Alarming News Alice the Camel

Alice the Camel Althouse

Althouse Always Right, Usually Correct

Always Right, Usually Correct America's North Shore Journal

America's North Shore Journal American Daily

American Daily American Digest

American Digest American Princess

American Princess The Anchoress

The Anchoress Andrew Ian Dodge

Andrew Ian Dodge Andrew Olmstead

Andrew Olmstead Angelican Samizdat

Angelican Samizdat Ann's Fuse Box

Ann's Fuse Box Annoyances and Dislikes

Annoyances and Dislikes Another Rovian Conspiracy

Another Rovian Conspiracy Another Think

Another Think Anti-Idiotarian Rottweiler

Anti-Idiotarian Rottweiler Associated Content

Associated Content The Astute Bloggers

The Astute Bloggers Atlantic Blog

Atlantic Blog Atlas Shrugs

Atlas Shrugs Atomic Trousers

Atomic Trousers Azamatterofact

Azamatterofact B Movies

B Movies Bad Catholicism

Bad Catholicism Bacon Eating Atheist Jew

Bacon Eating Atheist Jew Barking Moonbat Early Warning System

Barking Moonbat Early Warning System The Bastidge

The Bastidge The Belmont Club

The Belmont Club Because I Said So

Because I Said So Bernie Quigley

Bernie Quigley Best of the Web

Best of the Web Between the Coasts

Between the Coasts Bidinotto's Blog

Bidinotto's Blog Big Lizards

Big Lizards Bill Hobbs

Bill Hobbs Bill Roggio

Bill Roggio The Black Republican

The Black Republican BlameBush!

BlameBush! Blasphemes

Blasphemes Blog Curry

Blog Curry Blogodidact

Blogodidact Blowing Smoke

Blowing Smoke A Blog For All

A Blog For All The Blog On A Stick

The Blog On A Stick Blogizdat (Just Think About It)

Blogizdat (Just Think About It) Blogmeister USA

Blogmeister USA Blogs For Bush

Blogs For Bush Blogs With A Face

Blogs With A Face Blue Star Chronicles

Blue Star Chronicles Blue Stickies

Blue Stickies Bodie Specter

Bodie Specter Brilliant! Unsympathetic Common Sense

Brilliant! Unsympathetic Common Sense Booker Rising

Booker Rising Boots and Sabers

Boots and Sabers Boots On

Boots On Bottom Line Up Front

Bottom Line Up Front Broken Masterpieces

Broken Masterpieces Brothers Judd

Brothers Judd Brutally Honest

Brutally Honest Building a Timberframe Home

Building a Timberframe Home Bush is Hitler

Bush is Hitler Busty Superhero Chick

Busty Superhero Chick Caerdroia

Caerdroia Caffeinated Thoughts

Caffeinated Thoughts California Conservative

California Conservative Cap'n Bob & The Damsel

Cap'n Bob & The Damsel Can I Borrow Your Life

Can I Borrow Your Life Captain's Quarters

Captain's Quarters Carol's Blog!

Carol's Blog! Cassy Fiano

Cassy Fiano Cato Institute

Cato Institute CDR Salamander

CDR Salamander Ceecee Marie

Ceecee Marie Cellar Door

Cellar Door Chancy Chatter

Chancy Chatter Chaos Manor Musings

Chaos Manor Musings Chapomatic

Chapomatic Chicago Boyz

Chicago Boyz Chickenhawk Express

Chickenhawk Express Chief Wiggles

Chief Wiggles Chika de ManiLA

Chika de ManiLA Christianity, Politics, Sports and Me

Christianity, Politics, Sports and Me Church and State

Church and State The Cigar Intelligence Agency

The Cigar Intelligence Agency Cindermutha

Cindermutha Classic Liberal Blog

Classic Liberal Blog Club Troppo

Club Troppo Coalition of the Swilling

Coalition of the Swilling Code Red

Code Red Coffey Grinds

Coffey Grinds Cold Fury

Cold Fury Colorado Right

Colorado Right Common Sense Junction

Common Sense Junction Common Sense Regained with Kyle-Anne Shiver

Common Sense Regained with Kyle-Anne Shiver Confederate Yankee

Confederate Yankee Confessions of a Gun Toting Seagull

Confessions of a Gun Toting Seagull Conservathink

Conservathink Conservative Beach Girl

Conservative Beach Girl Conservative Blog Therapy

Conservative Blog Therapy Conservative Boot Camp

Conservative Boot Camp Conservative Outpost

Conservative Outpost Conservative Pup

Conservative Pup The Conservative Right

The Conservative Right Conservatives for American Values

Conservatives for American Values Conspiracy To Keep You Poor & Stupid

Conspiracy To Keep You Poor & Stupid Cox and Forkum

Cox and Forkum Cranky Professor

Cranky Professor Cranky Rants

Cranky Rants Crazy But Able

Crazy But Able Crazy Rants of Samantha Burns

Crazy Rants of Samantha Burns Create a New Season

Create a New Season Crush Liberalism

Crush Liberalism Curmudgeonly & Skeptical

Curmudgeonly & Skeptical D. Challener Roe

D. Challener Roe Da' Guns Random Thoughts

Da' Guns Random Thoughts Dagney's Rant

Dagney's Rant The Daily Brief

The Daily Brief The Daily Dish

The Daily Dish Daily Flute

Daily Flute Daily Pundit

Daily Pundit The Daley Gator

The Daley Gator Daniel J. Summers

Daniel J. Summers Dare2SayIt

Dare2SayIt Darlene Taylor

Darlene Taylor Dave's Not Here

Dave's Not Here David Drake

David Drake Day By Day

Day By Day Dean's World

Dean's World Decision '08

Decision '08 Debbie Schlussel

Debbie Schlussel Dhimmi Watch

Dhimmi Watch Dipso Chronicles

Dipso Chronicles Dirty Election

Dirty Election Dirty Harry's Place

Dirty Harry's Place Dissecting Leftism

Dissecting Leftism The Dissident Frogman

The Dissident Frogman Dogwood Pundit

Dogwood Pundit Don Singleton

Don Singleton Don Surber

Don Surber Don't Go Into The Light

Don't Go Into The Light Dooce

Dooce Doug Ross

Doug Ross Down With Absolutes

Down With Absolutes Drink This

Drink This Dumb Ox News

Dumb Ox News Dummocrats

Dummocrats Dustbury

Dustbury Dustin M. Wax

Dustin M. Wax Dyspepsia Generation

Dyspepsia Generation Ed Driscoll

Ed Driscoll The Egoist

The Egoist Eject! Eject! Eject!

Eject! Eject! Eject! Euphoric Reality

Euphoric Reality Exile in Portales

Exile in Portales Everything I Know Is Wrong

Everything I Know Is Wrong Exit Zero

Exit Zero Expanding Introverse

Expanding Introverse Exposing Feminism

Exposing Feminism Faith and Theology

Faith and Theology FARK

FARK Fatale Abstraction

Fatale Abstraction Feministing

Feministing Fetching Jen

Fetching Jen Finding Ponies...

Finding Ponies... Fireflies in the Cloud

Fireflies in the Cloud Fish or Man

Fish or Man Flagrant Harbour

Flagrant Harbour Flopping Aces

Flopping Aces Florida Cracker

Florida Cracker For Your Conservative Pleasure

For Your Conservative Pleasure Forgetting Ourselves

Forgetting Ourselves Fourth Check Raise

Fourth Check Raise Fred Thompson News

Fred Thompson News Free Thoughts

Free Thoughts The Freedom Dogs

The Freedom Dogs Gadfly

Gadfly Galley Slaves

Galley Slaves Gate City

Gate City Gator in the Desert

Gator in the Desert Gay Patriot

Gay Patriot The Gallivantings of Daniel Franklin

The Gallivantings of Daniel Franklin Garbanzo Tunes

Garbanzo Tunes God, Guts & Sarah Palin

God, Guts & Sarah Palin Google News

Google News GOP Vixen

GOP Vixen GraniteGrok

GraniteGrok The Greatest Jeneration

The Greatest Jeneration Green Mountain Daily

Green Mountain Daily Greg and Beth

Greg and Beth Greg Mankiw

Greg Mankiw Gribbit's Word

Gribbit's Word Guy in Pajamas

Guy in Pajamas Hammer of Truth

Hammer of Truth The Happy Feminist

The Happy Feminist Hatless in Hattiesburg

Hatless in Hattiesburg The Heat Is On

The Heat Is On Hell in a Handbasket

Hell in a Handbasket Hello Iraq

Hello Iraq Helmet Hair Blog

Helmet Hair Blog Heritage Foundation

Heritage Foundation Hillary Needs a Vacation

Hillary Needs a Vacation Hillbilly White Trash

Hillbilly White Trash The Hoffman's Hearsay

The Hoffman's Hearsay Hog on Ice

Hog on Ice HolyCoast

HolyCoast Homeschooling 9/11

Homeschooling 9/11 Horsefeathers

Horsefeathers Huck Upchuck

Huck Upchuck Hugh Hewitt

Hugh Hewitt I, Infidel

I, Infidel I'll Think of Something Later

I'll Think of Something Later IMAO

IMAO Imaginary Liberal

Imaginary Liberal In Jennifer's Head

In Jennifer's Head Innocents Abroad

Innocents Abroad Instapundit

Instapundit Intellectual Conservative

Intellectual Conservative The Iowa Voice

The Iowa Voice Is This Life?

Is This Life? Islamic Danger 4u

Islamic Danger 4u The Ivory Tower

The Ivory Tower Ivory Tower Adventures

Ivory Tower Adventures J. D. Pendry

J. D. Pendry Jaded Haven

Jaded Haven James Lileks

James Lileks Jane Lake Makes a Mistake

Jane Lake Makes a Mistake Jarhead's Firing Range

Jarhead's Firing Range The Jawa Report

The Jawa Report Jellyfish Online

Jellyfish Online Jeremayakovka

Jeremayakovka Jesus and the Culture Wars

Jesus and the Culture Wars Jesus' General

Jesus' General Jihad Watch

Jihad Watch Jim Ryan

Jim Ryan Jon Swift

Jon Swift Joseph Grossberg

Joseph Grossberg Julie Cork

Julie Cork Just Because Your Paranoid...

Just Because Your Paranoid... Just One Minute

Just One Minute Karen De Coster

Karen De Coster Keep America at Work

Keep America at Work KelliPundit

KelliPundit Kender's Musings

Kender's Musings Kiko's House

Kiko's House Kini Aloha Guy

Kini Aloha Guy KURU Lounge

KURU Lounge La Casa de Towanda

La Casa de Towanda Laughter Geneology

Laughter Geneology Leaning Straight Up

Leaning Straight Up Left Coast Rebel

Left Coast Rebel Let's Think About That

Let's Think About That Liberal Utopia

Liberal Utopia Liberal Whoppers

Liberal Whoppers Liberalism is a Mental Disorder

Liberalism is a Mental Disorder Liberpolly's Journal

Liberpolly's Journal Libertas Immortalis

Libertas Immortalis Life in 3D

Life in 3D Linda SOG

Linda SOG Little Green Fascists

Little Green Fascists Little Green Footballs

Little Green Footballs Locomotive Breath

Locomotive Breath Ludwig von Mises Institute

Ludwig von Mises Institute Lundesigns

Lundesigns Rachel Lucas

Rachel Lucas The Machinery of Night

The Machinery of Night The Macho Response

The Macho Response Macsmind

Macsmind Maggie's Farm

Maggie's Farm Making Ripples

Making Ripples Management Systems Consulting, Inc.

Management Systems Consulting, Inc. Marginalized Action Dinosaur

Marginalized Action Dinosaur Mark's Programming Ramblings

Mark's Programming Ramblings The Marmot's Hole

The Marmot's Hole Martini Pundit

Martini Pundit MB Musings

MB Musings McBangle's Angle

McBangle's Angle Media Research Center

Media Research Center The Median Sib

The Median Sib Mein Blogovault

Mein Blogovault Melissa Clouthier

Melissa Clouthier Men's News Daily

Men's News Daily Mending Time

Mending Time Michael's Soapbox

Michael's Soapbox Michelle Malkin

Michelle Malkin Mike's Eyes

Mike's Eyes Millard Filmore's Bathtub

Millard Filmore's Bathtub A Million Monkeys Typing

A Million Monkeys Typing Michael Savage

Michael Savage Minnesota Democrats Exposed

Minnesota Democrats Exposed Miss Cellania

Miss Cellania Missio Dei

Missio Dei Missouri Minuteman

Missouri Minuteman Modern Tribalist

Modern Tribalist Moonbattery

Moonbattery Mother, May I Sleep With Treacher?

Mother, May I Sleep With Treacher? Move America Forward

Move America Forward Moxie

Moxie Ms. Underestimated

Ms. Underestimated My Republican Blog

My Republican Blog My Vast Right Wing Conspiracy

My Vast Right Wing Conspiracy Mythusmage Opines

Mythusmage Opines Naked Writing

Naked Writing Nation of Cowards

Nation of Cowards National Center Blog

National Center Blog Nealz Nuze

Nealz Nuze NeoCon Blonde

NeoCon Blonde Neo-Neocon

Neo-Neocon Neptunus Lex

Neptunus Lex Nerd Family

Nerd Family Network of Enlightened Women (NeW)

Network of Enlightened Women (NeW) News Pundit

News Pundit Nightmare Hall

Nightmare Hall No Sheeples Here

No Sheeples Here NoisyRoom.net

NoisyRoom.net Normblog

Normblog The Nose On Your Face

The Nose On Your Face NYC Educator

NYC Educator The Oak Tree

The Oak Tree Obama's Gaffes

Obama's Gaffes Obi's Sister

Obi's Sister Oh, That Liberal Media!

Oh, That Liberal Media! Old Hippie

Old Hippie One Cosmos

One Cosmos One Man's Kingdom

One Man's Kingdom One More Cup of Coffee

One More Cup of Coffee Operation Yellow Elephant

Operation Yellow Elephant OpiniPundit

OpiniPundit Orion Sector

Orion Sector The Other (Robert Stacy) McCain

The Other (Robert Stacy) McCain The Outlaw Republican

The Outlaw Republican Outside The Beltway

Outside The Beltway Pajamas Media

Pajamas Media Palm Tree Pundit

Palm Tree Pundit Papa Knows

Papa Knows Part-Time Pundit

Part-Time Pundit Pass The Ammo

Pass The Ammo Passionate America

Passionate America Patriotic Mom

Patriotic Mom Pat's Daily Rant

Pat's Daily Rant Patterico's Pontifications

Patterico's Pontifications Pencader Days

Pencader Days Perfunction

Perfunction Perish the Thought

Perish the Thought Personal Qwest

Personal Qwest Peter Porcupine

Peter Porcupine Pettifog

Pettifog Philmon

Philmon Philosoblog

Philosoblog Physics Geek

Physics Geek Pigilito Says...

Pigilito Says... Pillage Idiot

Pillage Idiot The Pirate's Cove

The Pirate's Cove Pittsburgh Bloggers

Pittsburgh Bloggers Point of a Gun

Point of a Gun Political Byline

Political Byline A Political Glimpse From Ireland

A Political Glimpse From Ireland Political Party Pooper

Political Party Pooper Possumblog

Possumblog Power Line

Power Line PrestoPundit

PrestoPundit Professor Mondo

Professor Mondo Protein Wisdom

Protein Wisdom Protest Warrior

Protest Warrior Psssst! Over Here!

Psssst! Over Here! The Pungeoning

The Pungeoning Q and O

Q and O Quiet Moments, Busy Lives

Quiet Moments, Busy Lives Rachel Lucas

Rachel Lucas Radio Paradise

Radio Paradise Rantburg

Rantburg Real Clear Politics

Real Clear Politics Real Debate Wisconsin

Real Debate Wisconsin Reason

Reason Rebecca MacKinnon

Rebecca MacKinnon RedState.Org PAC

RedState.Org PAC Red, White and Conservative

Red, White and Conservative Reformed Chicks Babbling

Reformed Chicks Babbling The Reign of Reason

The Reign of Reason The Religion of Peace

The Religion of Peace Resistance is Futile!

Resistance is Futile! Revenge...

Revenge... Reverse Vampyr

Reverse Vampyr Rhymes with Cars and Girls

Rhymes with Cars and Girls Right Angle

Right Angle Right Events

Right Events Right Mom

Right Mom Right Thinking from the Left Coast

Right Thinking from the Left Coast Right Truth

Right Truth Right View Wisconsin

Right View Wisconsin Right Wing Rocker

Right Wing Rocker Right Wing News

Right Wing News Rightwingsparkle

Rightwingsparkle Robin Goodfellow

Robin Goodfellow Rocker and Sage

Rocker and Sage Roger L. Simon

Roger L. Simon Rogue Thinker

Rogue Thinker Roissy in DC

Roissy in DC Ronalfy

Ronalfy Ron's Musings

Ron's Musings Rossputin

Rossputin Roughstock Journal

Roughstock Journal The Rude Pundit

The Rude Pundit The Rule of Reason

The Rule of Reason Running Roach

Running Roach The Saloon

The Saloon The Salty Tusk

The Salty Tusk Samantha Speaks

Samantha Speaks Samizdata

Samizdata Samson Blinded

Samson Blinded Say Anything

Say Anything Say No To P.C.B.S.

Say No To P.C.B.S. Scillicon and Cigarette Burns

Scillicon and Cigarette Burns Scott's Morning Brew

Scott's Morning Brew SCOTUSBlog

SCOTUSBlog Screw Politically Correct B.S.

Screw Politically Correct B.S. SCSU Scholars

SCSU Scholars Seablogger

Seablogger See Jane Mom

See Jane Mom Self-Evident Truths

Self-Evident Truths Sensenbrenner Watch

Sensenbrenner Watch Sergeant Lori

Sergeant Lori Seven Inches of Sense

Seven Inches of Sense Shakesville

Shakesville Shark Blog

Shark Blog Sheila Schoonmaker

Sheila Schoonmaker Shot in the Dark

Shot in the Dark The Simplest Thing

The Simplest Thing Simply Left Behind

Simply Left Behind Sister Toldjah

Sister Toldjah Sippican Cottage

Sippican Cottage SISU

SISU Six Meat Buffet

Six Meat Buffet Skeptical Observer

Skeptical Observer Skirts, Not Pantsuits

Skirts, Not Pantsuits Small Dead Animals

Small Dead Animals Smallest Minority

Smallest Minority Solomonia

Solomonia Soy Como Soy

Soy Como Soy Spiced Sass

Spiced Sass Spleenville

Spleenville Steeljaw Scribe

Steeljaw Scribe Stephen W. Browne

Stephen W. Browne Stilettos In The Sand

Stilettos In The Sand Still Muttering to Myself

Still Muttering to Myself SoxBlog

SoxBlog Stolen Thunder

Stolen Thunder Strata-Sphere

Strata-Sphere Sugar Free But Still Sweet

Sugar Free But Still Sweet The Sundries Shack

The Sundries Shack Susan Hill

Susan Hill Sweet, Familiar Dissonance

Sweet, Familiar Dissonance Tail Over Tea Kettle

Tail Over Tea Kettle Tale Spin

Tale Spin Talk Arena

Talk Arena Tapscott's Copy Desk

Tapscott's Copy Desk Target of Opportunity

Target of Opportunity Tasteful Infidelicacies

Tasteful Infidelicacies Tequila and Javalinas

Tequila and Javalinas Texas Rainmaker

Texas Rainmaker Texas Scribbler

Texas Scribbler That's Right

That's Right Thirty-Nine And Holding

Thirty-Nine And Holding This Blog Is Full Of Crap

This Blog Is Full Of Crap Thought You Should Know

Thought You Should Know Tom Nelson

Tom Nelson Townhall

Townhall Toys in the Attic

Toys in the Attic The Truth

The Truth Tim Blair

Tim Blair The TrogloPundit

The TrogloPundit Truth, Justice and the American Way

Truth, Justice and the American Way The Truth Laid Bear

The Truth Laid Bear Two Babes and a Brain

Two Babes and a Brain Unclaimed Territory

Unclaimed Territory Urban Grounds

Urban Grounds Varifrank

Varifrank Verum Serum

Verum Serum Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson Villanous Company

Villanous Company The Virginian

The Virginian Vodkapundit

Vodkapundit The Volokh Conspiracy

The Volokh Conspiracy Vox Popular

Vox Popular Vox Veterana

Vox Veterana Walls of the City

Walls of the City The Warrior Class

The Warrior Class Washington Rebel

Washington Rebel Weasel Zippers

Weasel Zippers Webutante

Webutante Weekly Standard

Weekly Standard Western Chauvinist

Western Chauvinist A Western Heart

A Western Heart Wheels Within Wheels

Wheels Within Wheels When Angry Democrats Attack!

When Angry Democrats Attack! Whiskey's Place

Whiskey's Place Wicking's Weblog

Wicking's Weblog Wide Awakes Radio (WAR)

Wide Awakes Radio (WAR) Winds of Change.NET

Winds of Change.NET Word Around the Net

Word Around the Net Writing English

Writing English Woman Honor Thyself

Woman Honor Thyself "A Work in Progress

"A Work in Progress World According to Carl

World According to Carl WorldNet Daily

WorldNet Daily WuzzaDem

WuzzaDem WyBlog

WyBlog Yorkshire Soul

Yorkshire Soul Zero Two Mike Soldier

Zero Two Mike SoldierFrank J. Tipler writes at Men’s News Daily:

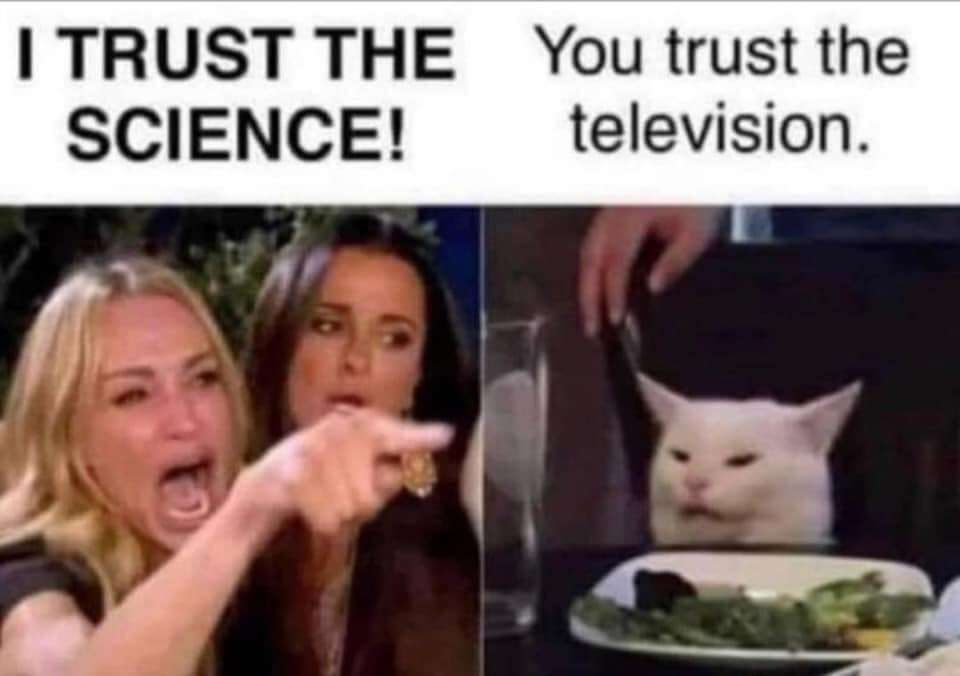

“Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts” is how the great Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman defined science in his article “What is Science?” Feynman emphasized this definition by repeating it in a stand-alone sentence in extra large typeface in his article.

Immediately after his definition of science, Feynman wrote: “When someone says, ‘Science teaches such and such,’ he is using the word incorrectly. Science doesn’t teach anything; experience teaches it. If they say to you, ‘Science has shown such and such,’ you should ask, ‘How does science show it? How did the scientists find out? How? What? Where?’ It should not be ‘science has shown.’ And you have as much right as anyone else, upon hearing about the experiments (but be patient and listen to all the evidence) to judge whether a sensible conclusion has been arrived at.”

And I say, Amen. Notice that “you” is the average person. You have the right to hear the evidence, and you have the right to judge whether the evidence supports the conclusion. We now use the phrase “scientific consensus,” or “peer review,” rather than “science has shown.” By whatever name, the idea is balderdash. Feynman was absolutely correct.

When the attorney general of Virginia sued to force Michael Mann of “hockey stick” fame to provide the raw data he used, and the complete computer program used to analyze the data, so that “you” could decide, the Faculty Senate of the University of Virginia declared this request — Feynman’s request — to be an outrage. You peons, the Faculty Senate decreed, must simply accept the conclusions of any “scientific endeavor that has satisfied peer review standards.” Feynman’s — and the attorney general’s and my own and other scientists’ — request for the raw data, so we can “judge whether a sensible conclusion has been arrived at,” would, according to the Faculty Senate, “send a chilling message to scientists…and indeed scholars in any discipline.”

According the Faculty Senate of the University of Virginia, “science,” and indeed “scholarship” in general, is no longer an attempt to establish truth by replicable experiment, or by looking at evidence that can be checked by anyone. “Truth” is now to be established by the decree of powerful authority, by “peer review.” Wasn’t the whole point of the Enlightenment to avoid exactly this?

We’ve sometimes referred, here, to a logical fallacy we have given the name of “Malcolm Forbes’ Demise.” Back when the balloon-riding mogul assumed room temperature, we happened to have read about it first in some trashy tabloid (reading the cover while waiting to pay for our groceries, of course). Now, 1990 being well before the maturity of the Internet as we know it today, and at the time not really caring about it too much, it was some time before we learned of this from any other source. So pretending for the moment we were forced to rely on a tabloid magazine — if we were to try to arrive at a “scientific” hypothesis about Mr. Forbes’ health, and engage in this “peer review” process done by “science,” the first step would of course be to establish the level of credibility of these trash-tabs. It’s very low, of course. And from that we would then have to conclude, tentatively, that Forbes is alive and well until we hear differently from a more reliable source.

According to the methods we are told are sound, that’s only reasonable!

According to the methods we are told are sound, that’s only reasonable!

A man of genuine logic and reason, on the other hand, would ask himself how likely it is that the evidence in hand would arrive, were there no truth behind the statement. Well, a better source would be desirable, for sure. But our exercise, being one of deriving conclusions from facts, rather than of gathering the facts, says we are deprived of that…so in the absence of that, would the rag print up the headline if Malcolm Forbes was not dead? The potential for this is peripheral at best. Would you bet money that Forbes is alive? Or that he’s dead? Use your common sense. He’s probably dead.

It seems a piddling distinction to make. And when you have the luxury of demanding information out of Google on a whim, it does become mostly meaningless. But all human affairs are not scrutinized by the robots of Google. So “consider the source” remains good advice, but that’s all it is. It doesn’t decide the entire question. This is a mistake commonly made by esteemed experts in the scientific community, as well as by us “peons.”

Another way we’ve been putting it: If someone known to you to possess appealing attributes says something that is known to be false, how do you react? How about if someone known to you to possess harmful attributes, says something known to be true? Does it then become untrue? What if the “knowns” are not entirely known, but mostly-known?

I lately made the acquaintance of another blogger. “Made the acquaintance of” means “got into a big ol’ cyber-dustup S.I.W.O.T.I. (Someone Is Wrong On The Innernets) argument with.” Late in the exchange I had noticed our real disagreement wasn’t with regard to the facts, or the conclusions to be reached from them, but rather with the method used for deriving conclusions from facts. You see, he had come off a very intoxicating high, having successfully bullied all sorts of folks to stop looking at something, and I kept looking at it. So he started telling half-truths about the study being recanted, which turned out not to be true; then, all other approaches having been exhausted, he started having an electronic hissy-fit trying to get me to ignore what he wanted me to ignore.

Noting that what the study purported to prove wasn’t even anything outside the realm of agreement between the two sides, I made this observation:

Your blog is fascinated with, and named after, a canard that was started (unintentionally) by H.L. Mencken; mine is fascinated with, and named after, an ancient library administrator who figured out the size of the Earth. So you’re sort of a “Bizarro Eratosthenes” from an anti-matter universe: Instead of encouraging people to look at things, you’re encouraging them to look away. I’m a software engineer, and from your comments it appears you are a (failed?) lawyer.

It’s the “fruit of the poisoned tree” doctrine. Cop illegally enters my apartment and catches me building a bomb, or torturing my kidnapped toddler, or writing a confession in my diary about having murdered somebody — and the law has to pretend it never happened. Yes, I know the doctrine is refined across time and it’s a good deal more complex than this, but the fundamental principle remains: We are to allow our lawyers to decide for us what “truth” is, and they are to instruct us to disregard big chunks of real truth.

There is a skill involved in this, and it is a learned skill passed down through the generations from parent to child. Today it is all but extinct: Isolating a claim from those who make it and argue about it, focusing only on the claim, exerting one’s mental energies toward figuring out if there’s truth to it or not.

Our overly-mature society has lost this. We look to the “experts” to figure it out for us, and trust them implicitly even in situations where we have no idea who they are, let alone what their agenda might be. Much of the erosion has been relatively recent. I trace it to the early 1960’s, to mid 1950’s; the Warren Court had transformed the “Fruit of the Poisoned Tree” doctrine into an iron fisted jurisprudence requiring judicial and enforcement officials of the law to pretend false things were true and true things were false.

The good news is that we always have the potential within us for a revival. It is interwoven into our DNA. If you’re about to crawl under a car, you will automatically become a highly skilled philosopher, dedicated to love of wisdom and love of truth, as you set about the task of figuring out if the jack stand is worthy of your trust. We rekindle this spirit by doing work, and we rekindle it quickly, forcefully, keenly, by doing dangerous work.

We allow it to atrophy when we shirk our responsibilities, when we become comfy, when we allow our existences to whither and shrivel into these little menageries of iPods, iced coffee drinks and video games. That is when we curl up into a fetal position and look for someone else to tell us what truth is. That is when we stop peeking into water wells, imploring our aristocrats, our superiors, our overseers, to form their communities and publish their papers and define their collectives.

You see, “peer review” is actually a misnomer. A peer is a relative term, applied to someone who possesses equal stature. This is a process for declaring communities of demigods, to stand over us and give us orders about what to think, to strip us of our God-given autonomy, independence, masculinity and resolve.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.